Memories, monuments and myths

A child of the Iraqi diaspora, Rand Abdul Jabbar explores the culture of a past she missed out on.

by Charles Shafaieh

For most of Rand Abdul Jabbar’s life, Iraq existed more in her imagination than in reality. Born in Baghdad in 1990, the artist and designer left the country for Abu Dhabi at age five and only returned, to visit, in 2018. Rather than through lived experiences, the country took shape in her mind as an amalgamation of childhood memories, family stories, and emotions conjured by heirlooms collected by her parents.

Among those memories was the scent of gardenias, which she associated with her maternal grandfather’s house. In 2017, as part of her Reconstructions series, Jabbar created a sculptural installation named after the plant. A white, conical vessel made of plaster protrudes from the wall, its large opening filled with gardenia-infused oil. On the exhibition’s opening day, a Lebanese woman told Jabbar the fragrance reminded her of home. What this stranger did not know was that she, not the artist, had the first-hand relationship to gardenias—Jabbar’s memory of her grandfather’s home was not hers but her mother’s. Continuous retelling had transferred the memory to Jabbar herself.

Attempting to understand her relationship to her place of birth—an at times complex fusion of fact and fiction—has guided much of Jabbar’s career. “Iraq is vivid in my memory, but because of my detachment and displacement, I always felt that I didn’t have the authority or agency to engage with a place that is actually foreign to me,” she says.

Her impostor syndrome began to subside when she was invited to co-create the Iraqi pavilion for Dubai Design Week in 2016 with Hozan Zangana, an Iraqi Kurdish designer who is based in the Netherlands. Although both are from the diaspora, they had markedly different upbringings. What they shared, however, was a connection to Iraq’s ancient foundation. “We did not think of Iraq as a social or political construct but as land, geography, and everything that archaeology has uncovered within it,” she explains. “Archaeology is about digging and searching for lost and fragile narratives. It’s about trying to connect to a place with which you’re unfamiliar, almost like trying to rediscover your history or your ancestry. That was our starting point.”

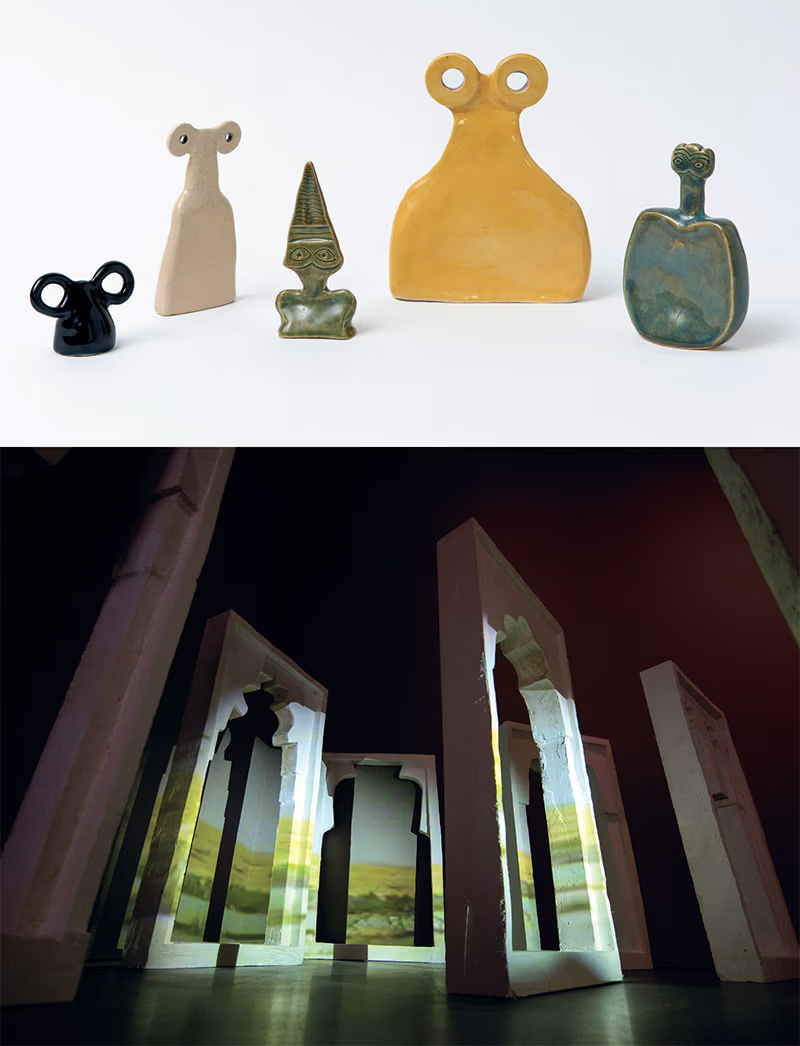

Where Myths Are Born of Mud and Desire, at Desert X AlUla 2024, recounts an allegory of cosmic events and ancestral beliefs, contemplating our quest for meaning and purpose. It describes the intertwined nature of life and loss, emphasising resilience and gesturing at renewal. Photograph by Lance Gerber, courtesy of Royal Commission for AlUla.

“My connection to clay, mud-brick architecture, and earthen architecture came when I went back to Iraq in 2018. We’re a clay culture. Seeing the landscape and its conditions prompted me to say, ‘This has to be clay, and I want to see where it goes.’”

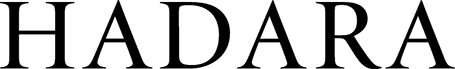

Research into their shared past led Jabbar and Zangana to create Excavations, a set of small sculptures that referenced historical objects—figurative statues, fragments of buildings including ziggurat walls and minarets—but with subtly altered forms. The objects seem at once ancient and modern. Some are coloured with bright shades of blue and red in sharp contrast to the black, sand-like, crumb rubber in which they were placed, appearing as if just unearthed or at risk of disappearing again.

Jabbar continues this meditation on forms in her ongoing work Earthly Wonders, Celestial Beings, which she began in 2019 and which, in 2022, won her the Richard Mille Art Prize. Akin to Excavations, the collection’s over 100 pieces take inspiration from Mesopotamian items, whether trees depicted in reliefs, sculptures of women, cuneiform writing, or jewellery. A key difference is their material and method of construction. Whereas the earlier work drew from her architecture background in using 3D digital modelling, these often-minute pieces are hand formed in clay and then glazed.

“My connection to clay, mud-brick architecture, and earthen architecture came when I went back to Iraq in 2018,” she says. “We’re a clay culture. Seeing the landscape and its conditions prompted me to say, ‘This has to be clay, and I want to see where it goes.’”

Not only does clay reference Iraq’s past, the act of making with it gives Jabbar access to Iraqi culture and history in a way she did not possess previously. When Jabbar was an architecture student, “Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Thinking Hand was an influential book for me,” she says. “He argues that we’ve lost our connection to embodied knowledge, as opposed to cerebral knowledge. Using clay, there’s a sense of ancestral knowledge referenced in the gestures and forms that continue to repeat. Connecting to a material that is very much part of the DNA of this place really freed me.”

Earthly Wonders, Celestial Beings (2019 – ongoing), top. Adopting clay as a medium, this collection, inspired by Mesopotamian items, is hand-formed and glazed. …and the river washing its feet (2019), above. This series of casts was produced from moulds originally fabricated for the reconstruction of the Minaret of Anah in 2012. Top: Ismail Noor, courtesy of Rand Abdul Jabbar; Bottom: Daniella Baptisa, courtesy of Art Jameel.

Clay takes Jabbar’s exploration of forms in unexpected directions, as her specific allusions to Iraqi sources naturally and unconsciously transform into abstract shapes with more universal resonances. “You might have a general idea of the form you’re thinking about, or at least the sort of gesture, but clay has a mind of its own. It’s quite easy to shape and intuitive in the way you work with it, but it leads you down its own path.”

Simply reproducing objects from the past would violate her aversion to nostalgia, not least because she is aware that her own childhood memories are corrupted. Her distaste for romanticising the past manifests in her 2019 installation …and the river washing its feet, commissioned by Dubai’s Art Jameel and produced in collaboration with archaeologist Yousif Al Diham. The work concerns the strange history of the minaret of Anah, a town on the Euphrates River. What began with the impulse to learn more about where her mother’s family lived became an interrogation of the community’s attachment to this building, which was first erected in the 11th century. Before construction of the hydroelectric dam that flooded the area in the 1980s and forced Anah’s citizens to leave, the minaret was dismantled and reconstructed in the new town. It was then destroyed by Al Qaeda in 2006 and rebuilt—only to have this reconstruction destroyed, in 2016, by ISIS. Yet another version has since been built.

The installation features gypsum casts of the minaret’s carved niches from the 2012 iteration. Projected onto them are videos of Al Diham’s uncle singing a song about loss to his young children on the riverbank, before the town’s destruction, as well as footage of the Euphrates flooding.

Excavations, developed with Hozan Zangana, proposes an exploration of the multi-layered histories embedded in a shared geography. Photograph by Petra Hesmerg, courtesy of Rand Abdul Jabbar.

“As an artist, I question what it means to rebuild a reconstruction of a reconstruction of a reconstruction,” she says. “I’m looking instead at ways in which an object can serve as a tool to unravel the narratives around it and present a story of all the events and forces that have shaped it, while also reflecting on how we mark those events in our built environment. When you reconstruct something perfectly and seamlessly, you negate everything that happened to it. So even if you rebuild, how do you still point to markers of time and give them place to be part of the history of this object and of this place?”

Jabbar’s practice resists calcification. Earthly Wonders, Celestial Beings remains open-ended, and her research for that project in turn inspired the sculptural shapes of her most recent work, Where Myths Are Born of Mud and Desire. On view earlier this year at Desert X AlUla, it explores cross-cultural myths about the planet Venus that concern the cycle of life, death, and resurrection. Drawing on her experiences as an intern for the architect Zaha Hadid, who emphasised the importance of fluidity across scales, she translates the impulses behind her earlier delicate work into the creation of monumental objects. Among the symbols on which she focuses is the crown as “a metaphor not for power or dominance but for knowledge and wisdom,” which will serve as the focal point of an upcoming piece. It will feature in her show at Lawrie Shabibi in Dubai in November that expands her earlier explorations of myth-making and storytelling through iconography. As with her previous work, it surely will lead her to more questions than answers.