Moments of creation

For designer and architect Abeer Seikaly, there is something invisible and intangible at the heart of the things we make.

By Charles Shafaieh

Abeer Seikaly is fascinated by the nets that Emirati fishermen have staked their livelihoods on for centuries. Obsessed with fabric structures broadly, the Jordanian-Palestinian architect and designer accepted an Abu Dhabi-based artist residency in order to study these intricately knotted tools up close.

After arriving from Amman in late 2024, Seikaly asked a retired pearl diver to show her how to make them by hand. She initially thought this would help her develop a piece which incorporated her research on similar Jordanian crafts, creating a bridge between the two countries. But as she spent time with him, the nets themselves receded from focus. Instead, her experience of making—especially her relationship with the diver, as he demonstrated his techniques and told her stories—took on heightened significance. The net became merely a manifestation of this shared experience and gained potency as a metaphor in which his ancestral memory, her personal associations, and their cross-cultural dialogue intertwined.

Seikaly’s time with the diver—which may inspire an experimental film—challenges a common hierarchy in Western design: that product is always more important than process. Furthermore, how something looks to the eye or how well it photographs too often becomes the only concern, for designer and public alike. Seikaly, however, has long understood that objects are much more than this.

Abeer Seikaly photographed by Sueraya Shaheen.

“We continue to think about architecture as a physical structure, but it’s not,” she says at her home in Abu Dhabi, her hands busy as she fiddles with a piece of mesh. “It involves many different entities, collaborators, and stakeholders. It’s about encounters—meeting people and connecting with them. It’s about community. It’s a process of becoming, of making, and of setting up a space to feel comfortable and connected.” The most important aspects of any work of design, in other words, are invisible, silently and poetically embedded deep within them.

This, she says, is as true for fishing nets as for what we cherish most. “Home,” for example, has long meant more than a building to her. “It’s not tangible,” she says. “It’s connected to childhood memories, family, and friends. It’s something that continually evolves, it has to do more with values and principles of connection than the thing itself.” For example, many of her works draw inspiration from the woven, mobile tents made by Bedouin women in Jordan’s southeastern Badia region, whom she frequently employs to construct her pieces. While she finds these tents themselves beautiful, she places even more emphasis on how their creation serves as an embodied connection to past traditions. Their weaving brings women together in work as well as in song and storytelling, and strengthens community ties.

Her youthful memories of her own home are vivid and formative. When she was five years old, an architect visited her family with a model of their future house. For the next two years, she accompanied her father to the building site and watched as this miniature plan became a habitable space. It was an act of translation and transformation that typifies how she considers her approach to her work today. “Between the house model and the building, there’s a space in between: a moment of creation, a movement, a realisation,” she explains. “One can think about it as a moment of tension, of compression. There is something pulsing, quite literally. This is the same description I would give for the creative process—a pulsating heartbeat.”

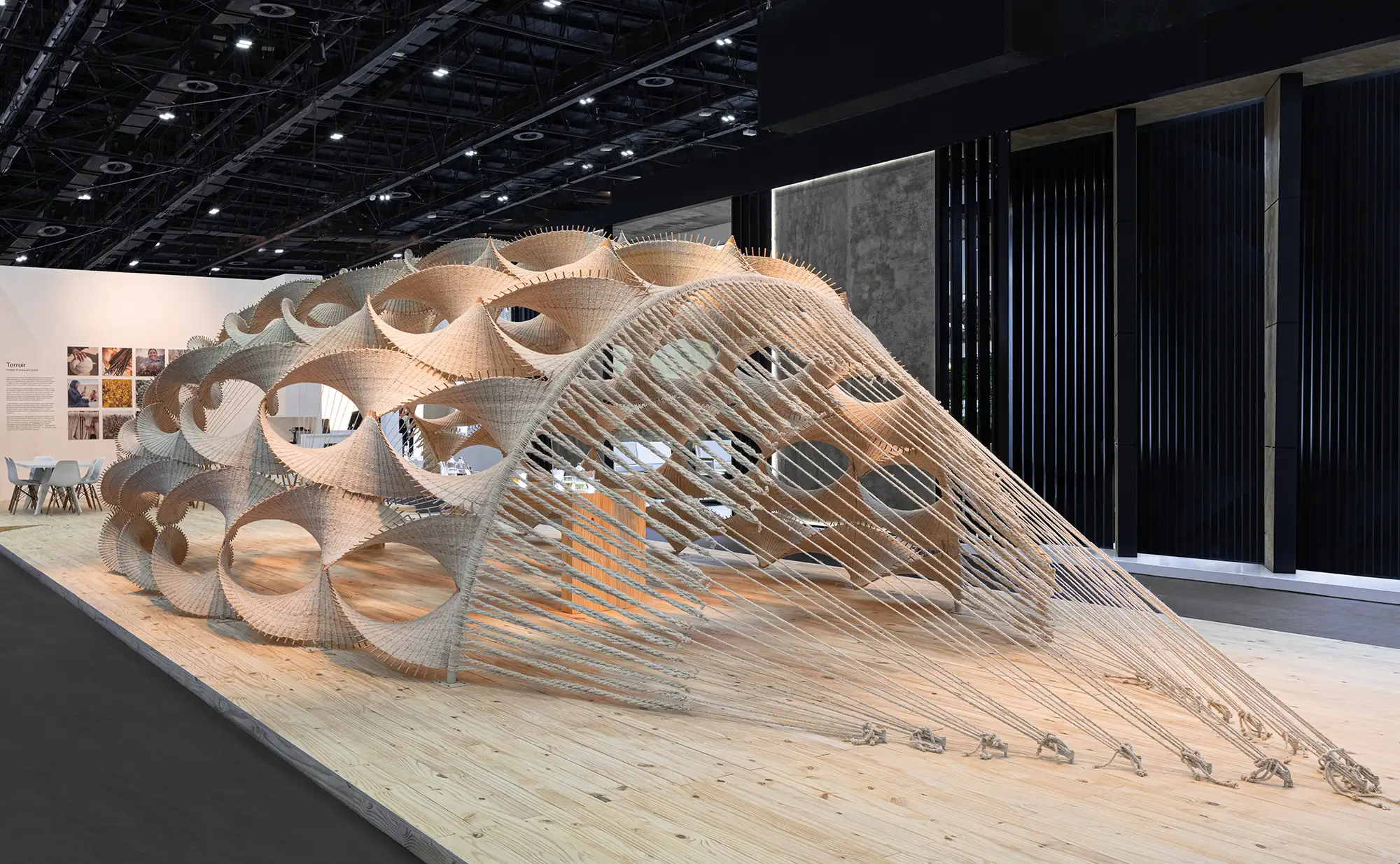

Opening image: Terroir (2022–ongoing). A handwoven structure that merges traditional Bedouin weaving techniques with contemporary design practices. Above, Constellations 2.0 Object. Light. Consciousness (2023). A suspended light sculpture of thousands of Murano glass tiles, handwoven into a structural mesh. Terroir photo by Rami Mansour. Constellations by Abeer Seikaly.

No wonder then that her pieces often convey a sense of movement and dynamism. Terroir (2022–ongoing) pays homage to the Bedouin ground loom—their “nucleus of communal interaction,” she says—and en- larges it into an occupiable cultural space, illustrating how traditional craft can inform contemporary design. These looms, when lined with layers of yarn pulled taught, exude a high degree of energy and tension. Seikaly pushes this further, though, by making Terroir’s woven form into a series of undulating spirals that appear to spin into infinity.

Weaving a Home (2020–ongoing) is a similarly rhythmic design, the most recent iteration of which is on view at the Qatar Pavilion at the Venice Biennale until November 23. Cell-like in appearance, these domes are lightweight, durable enclosures designed to provide shelter for people in need. Like Bedouin tents, they are collapsible. They also draw on these tribes’ deep-seated attention to sustainability as well as dissolve the distinction between fabric and structure. Seikaly’s earlier iterations were solar-powered, but now she seeks further inspiration from the Bedouin by using a material they have long celebrated: goat hair. “When you turn it into rope, it’s stronger than steel,” she says. “When it rains, the fibres in these tents expand, which creates a tightness that doesn’t allow water to seep in. When it’s hot, it contracts, allowing air to pass through.”

Weaving a Home (2020), top, a prototype of the dynamic dome shelter. Above, Seikaly applies the final touches to the handwoven fabric strips of her Terroir structure. Top image: Hussam Da’na, courtesy of Abeer Seikaly; Above by Abeer Seikaly.

Whatever form Weaving a Home may take, one certainty is that each aspect of the structure will be bound together, literally—as they are in all of Seikaly’s work, whether a chandelier comprised of 5,000 Murano glass tiles whose intricate, interwoven mesh structure takes inspiration from khoos, the Bedouin tradition of palm-branch weaving, or the hand-stitched wall-hangings that reference a carpet made by her great grandmother. “This is a holistic system. The sum of the parts creates the whole,” she explains. “If you remove one piece, the whole thing falls.”

Critical to this system are those who make and use the work. In the case of Weaving a Home, she stresses that what matters most is the empowerment and dignity these shelters provide their residents. “How can you engage people in the process and make them feel they have a sense of agency in terms of making decisions and developing things?” she asks. One answer that excites her is creating an open-source model. “Then people in different parts of the world can apply this form or the principles behind it using their own materials.” While she admits she isn’t ego-less, she says that neither her signature as the maker nor her style are important. She is just as much an equal part of the system as any other component.

Meditating on these fundamental issues brings to her mind a story about Buckminster Fuller, another architect obsessed with spheres and domes, whom she admires. “He was walking along Lake Michigan one day, contemplating the end, when suddenly he experienced a vision,” she recounts. “He found himself wrapped in a luminous sphere floating above the ground while a voice said, ‘You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the universe.’ That is a profound idea. Once you think about yourself as a channel, as part of a larger whole, the way you approach your work becomes totally different.” It prompts her to remember her purpose as an architect. “I always try to remind myself that my role is to serve.”