New Focus On Urban Landscape

Sharjah Triennial aims to raise awareness about architecture and urbanism in the region and how they impact the way we live.

BY HELEN JONES

The urban landscape across the Gulf region is changing rapidly. Even as it focuses on the future, the region increasingly wants to preserve the architectural past. Sharjah, with its history as a multi-ethnic port on Indian Ocean trade routes, where modern and older buildings sit side by side, is a fitting location to assess architectural trends and issues in the region.

Sharjah is building on its reputation as the cultural heart of the UAE with the launch of a new international event focused on architecture. The Sharjah Architecture Triennial will begin in November and is the first of its kind in the Arabic-speaking world. It will explore ideas and raise public awareness about architecture and urbanism in the Middle East, North and East Africa, and South and South East Asia (MENASA).

The Triennial, which will be held every three years, will explore how to create more humane and socially responsible cities. “This is a crucial moment in the understanding and development of architecture and urban planning of the MENASA region,” says Sheikh Khalid bin Sultan Al Qasimi, chairman of the Sharjah Urban Planning Council and the event’s founder. The Triennial “will offer an accessible platform for critical reflection on the social and cultural issues that we face at both regional and international levels.” Bringing together architects, academics, urban designers, government bodies, artists, students and the general public can lead to “new ways of designing cities,” he adds.

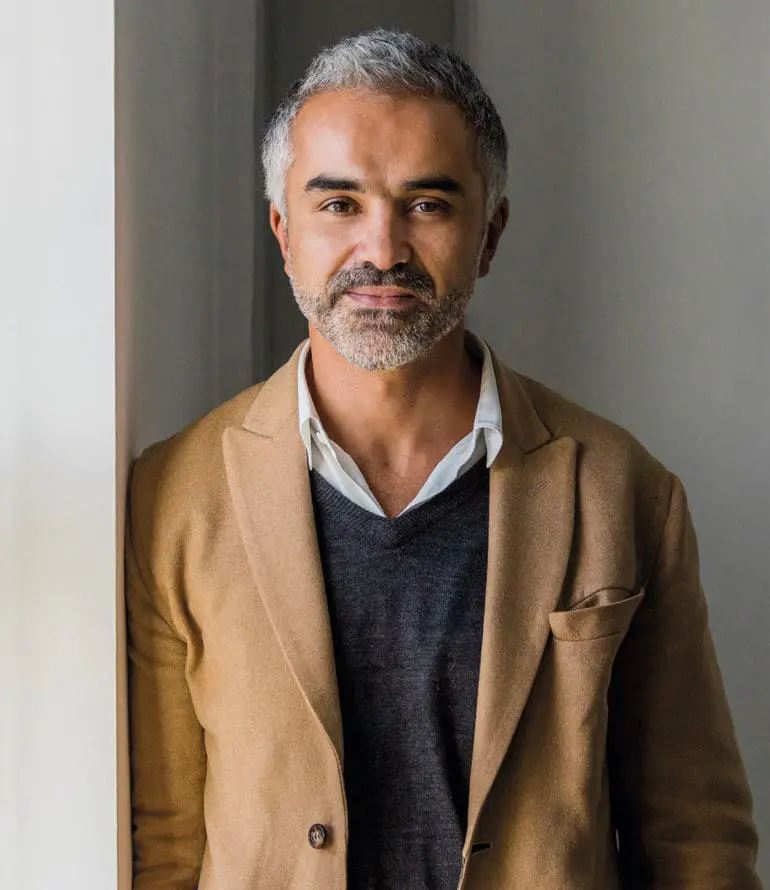

Over the course of three months, the Triennial will host an exhibition and a series of public events, talks, panels, film and music performances at multiple sites across the emirate. It is curated by the highly regarded architect, urban designer and researcher, Adrian Lahoud, dean of the School of Architecture at the Royal College of Art in London. Lahoud has written extensively about environmental change with a focus on the Arab world and Africa and is involved in an experimental research project bringing together scientists, artists, architects, activists and scholars across a wide variety of fields to explore the practical and philosophical implications of climate change.

Lahoud says the Triennial “seeks to engage both established as well as emerging architecture and urban practitioners, artists, and thinkers by commissioning work for the exhibition opening on November 9th, as well as initiating research and public forums around specific social and environmental conditions in Sharjah, the UAE, and internationally.”

The Triennial aims to question what architecture means in the Middle East, Africa and Asia and its impact on societies and ways of living. It will also challenge clichéd Western views of architecture in the region. “This is something that I feel has been addressed in other disciplines such as contemporary art and anthropology. However, it feels yet to be seriously addressed in architecture,” Lahoud says. “The clichés are prevalent in various ways —in the major architecture biennials and exhibitions, where emphasis on the traditional and the local denies non-Western practices any contemporaneity—as well as in academia, practice and the theory of architecture.”

The Triennial will also address the particular difficulties faced by architects, scholars, planners and artists in the Middle East, Africa and Asia. These range “from non-existent or fragmented archives to restrictions on travel, or the absence of institutional support and access to funding,” Lahoud says. The Triennial “aims to respond to this situation by initiating an archive of social and spatial experimentation, laying the groundwork of a lasting resource for generations of architects, scholars, planners and artists to come,” he adds.

The inaugural Triennial’s theme is “Rights of Future Generations.” While rights have expanded massively across the globe, “this expansion has failed to materially address long-standing challenges around environmental change and inequality,” Lahoud says. “A focus on access to health, education, and housing as individual rights has obscured collective claims such as rights of nature and environmental rights.”

Climate change is especially pertinent to the MENASA region and to architectural projects, but, as Lahoud explains, “Sites, regions and populations which climate change will affect and already affects most immediately and irreversibly are the same ones that face regimes of global socio-economic exploitation. It is therefore fundamental for the field of architecture to address these conditions in making visible and therefore complicit the relation of the built environment to land grab and resource extraction.” He sees a need to challenge the Western view that the environment is “a threat that needs to be contained and consumed rather than interacted and lived with.”

In the run-up to the Triennial, several panel discussions have already been held, featuring distinguished speakers from around the world. The first one focused on housing and domesticity, the second looked at the design of educational spaces and their impact on the aspirations of young people and the third debated environmental and ecological issues. Within these discussions the Triennial explored new concepts of buildings, cities and landscapes.

Within its wider theme the Triennial will question how inheritance, legacy and the state of the environment are passed from one generation to the next and how decisions taken now will have long-term inter-generational consequences. “We are connected to future generations through present decisions, but how do we negotiate with a generation that is yet to exist?” Lahoud asks. “What does it mean to articulate this intergenerational relationship in terms of rights to cities, to environments, to memories, to traditions, and histories?”

With these questions in mind, the Triennial has invited Ambassador Lumumba Di-Aping, the Sudanese diplomat who represented developing countries as chairman of the G77+China at the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Change Conference, to bring together United Nations representatives, government officials, international rights groups, and members of relevant civil society organisations to form a Rights of Future Generations Working Group. Members of the Working Group will be announced in September. Its mission is “to advance the protection of future generations’ fundamental rights in a world where climate change is dramatically shifting along socio-economic, legal, gender, racial and political dimensions.” The Working Group will produce The Sharjah Charter to be presented at The Sharjah Summit at the Triennial.

The Triennial’s organisers are keen to get young people involved in the event. “The idea is not only to invite young people to take part but also to find ways in which the Triennial can support already existing networks and practices of students and emerging architects, designers and thinkers,” Lahoud says. By engaging the public and young people in various discussions and events, the Triennial is expected to continue to have an impact in the future. “We hope these initiatives will continue and grow beyond the timeframe of the exhibition,” Lahoud says. This could manifest through the publications programme, the commissions which will develop and continue beyond their manifestation in the exhibition and the research instigated that will support future projects.