Language, translation and collateral damage

Iraqi novelist Sinan Antoon’s latest work, Fihris, uses the story of two friends to meditate on catastrophe and destruction, as well as one’s ties to one’s cultural home despite migration. Why, as a bilingual writer in the US, he chooses Arabic as the medium of his art.

WORDS BY CHARLES SHAFAIEH

Language is the medium in the art of writing. The connotations, the evolution of meanings, the rhythm of words. Bilingual writers face a dilemma: which language to choose?

Although living in the US since 1991, Sinan Antoon, a Baghdad-born writer and associate professor of Arabic literature at New York University (NYU), favours Arabic for his poetry and novels, such as the award-winning Wahdaha Shajarat al-Rumman, which the author himself translated into English as The Corpse Washer.

“I think most writers would love to be read by everyone—and English of course affords one a large audience—but one of the reasons I write in Arabic is for all those readers who read no other language,” Antoon tells me on a brisk autumn morning when we meet at a Manhattan coffee shop.

Literature in translation accounts for just 3% of the US book market. Of those titles, only a small number are translated from Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and the other major languages of western Asia, and even fewer attract critical attention or receive prizes. This status quo gives those bilingual writers who aspire to fame or fortune little incentive to write in their first languages.

Antoon privileges different rewards. “In the past 10 years, I’ve realised that for those in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere in the region, these novels in Arabic have become much more important and visceral, considering everything that has happened there. I call those readers my ‘front-row audience.’ I see them more closely and their responses matter more to me. I don’t want to lose them.”

In addition to the issue of audience, a writer’s choice of language often relates to memory and the intimate experience with a language’s unique textures and rhythms. Samuel Beckett, for example, eschewed English for French as a means of breaking all emotional connections with his writing; a word like “mother” carried significant psychological baggage for him that its French equivalent did not. Antoon’s decision lies on the opposite end of the spectrum. “When I moved to America in the pre-Internet era, the thing I missed most was the language,” he says. “It’s a cliché, but Arabic is in a way a home for me. I’m reminded of Sargon Boulus, the late poet and my friend who left Iraq for America, when he said that Arabic is the umbilical cord that linked him to his people and culture, the plant that he nurtured every day.”

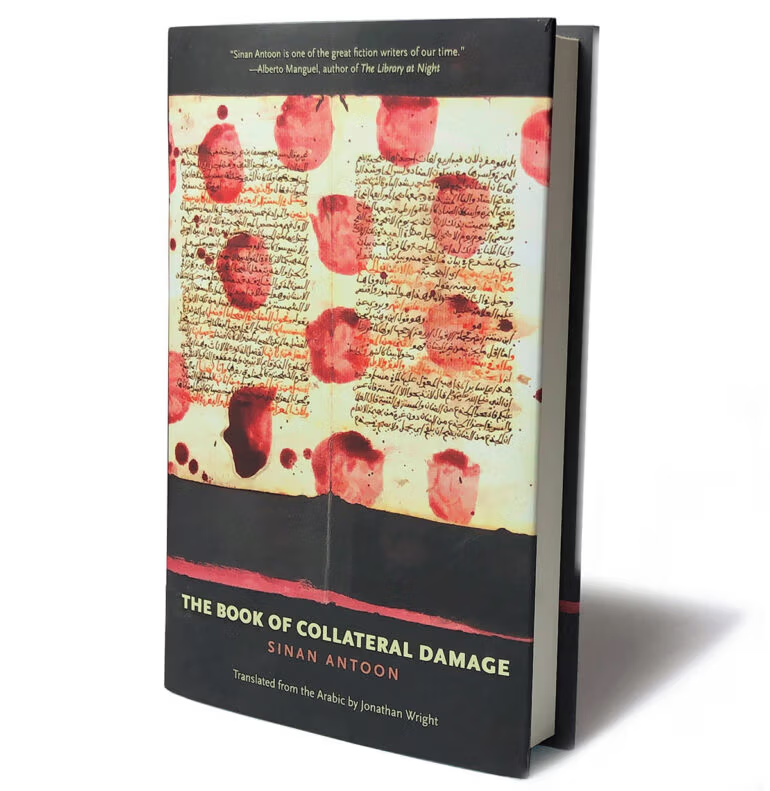

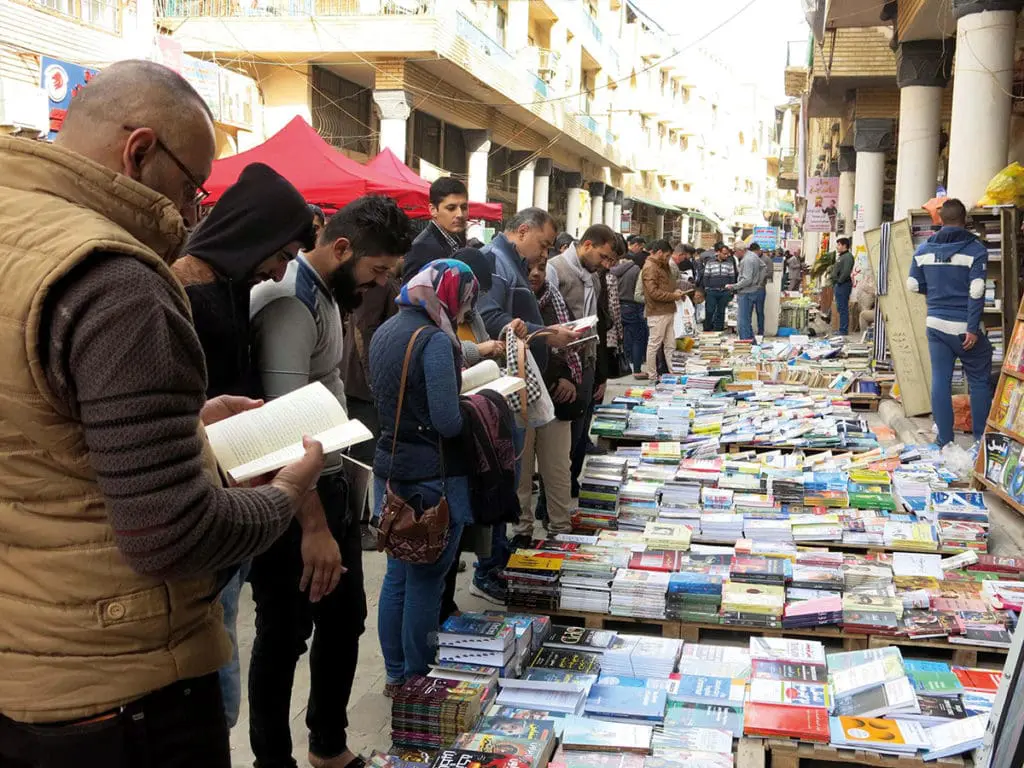

That desire for a connection between an immigrant and his birthplace, and that relationship’s ties to language, manifests itself throughout Antoon’s fourth novel, Fihris (The Book of Collateral Damage), which was recently published in English by Yale University Press. Its two protagonists are both Iraqis obsessed with literature. Nameer, a writer and academic from Baghdad, teaches Arabic literature at NYU, while Wadood runs a small bookshop on Baghdad’s Al-Mutanabbi Street that Nameer visits upon a return trip in 2003 as a translator for documentarists. During their first conversation, Wadood mentions his impossible project: archiving everything that has been destroyed in the recent invasion. The catalogue of lives cut short by unjust violence, which at present only encompasses the war’s first minute, assumes the form of a series of poetic autobiographies and elegies in which not just people but a tree, stamp album, Persian rug, and other unexpected objects and animals speak about their existence before they are consumed by flames, exploded in missile strikes, or crushed under rubble. These passages become interspersed with Nameer’s experiences as an immigrant in America—a life that takes on increasing shades of Wadood’s perspective as Nameer becomes consumed by these vignettes. The narrative that results slowly confuses a firm sense of beginnings and endings or fixed identities as it rejects the clear-cut narrative arc found in most contemporary literature.

This polyphonic structure embodies the novel’s sustained meditation on catastrophe in its various forms, both physical and psychological. “If I were to have written a linear narrative, it would have betrayed Wadood and the idea of a book about destruction as well as the impossibility of both putting together the fragments and of redemption,” Antoon argues. “It has to have a non-ending. And this also ties in with Nameer’s position as a writer from afar and the ethics of that act. How does someone write about Iraq, Syria or Palestine when they’re not there without hijacking the voices they’re writing about? Endings and beginnings are thus very political, too.”

The novel’s inventive patchwork form, which includes extensive references and quotes from Walter Benjamin and other European, American, Arab and African writers, also exemplifies the worldly cosmopolitanism of Iraqi culture, both recent and distant, and Arabic’s history. “Arabic is a sponge that internalised so much from Aramaic, Persian, and other languages,” Antoon says. “There are subtle gestures to this throughout the book, such as the reference to the twelfth-century Persian poem The Conference of the Birds by Farid ud-Din Attar in the opening and closing passages. It would be disingenuous to present some sort of monolithic Arab or Iraqi world, because we live in a world where there is so much overlap and interconnectedness. Some of the most fascinating points in the history of our species are moments of translation, and not just linguistic ones. Globalisation is not a recent phenomenon!”

Translation is itself a kind of new beginning, and one which is often misunderstood. Like all writing, it always fails to some degree in conveying an author’s depiction of sentiments, things, or people, but when done well its benefits far outweigh its deficiencies. “I am against those who harp on loss in translation,” Antoon says. “In my novels, the dialects, which are so embroiled in politics and nationalism, are lost, but that’s not legible to someone who doesn’t know the original. To again quote Boulus, what’s most important is what remains after translation. With, say, poetry, translation is a means to internalise the rhythms and words of those whose work I want to inhabit. It’s also an important political act to translate from what the United States government calls ‘strategic languages.’ Because of that, I always try to disrupt certain narratives about that part of the world.”

One site of such disruption and cultural expansion is Sharjah, whose international book fair is where Antoon first met his Indian publisher. “Someone living in Sharjah read my poems in English and wanted to translate them into Malayalam,” he recounts. “It made me so happy, going to that section of the fair. Thinking more about the cultures of the Indian Ocean is one way of realising the richness of our history and of moving away from the Eurocentric algorithm of looking at the world.”

Such joys redefine literary success and make evident that fruitful careers can be fostered independent from an English-language publishing industry that too often views Arab and Persian literature as instruments of forensic interest. “Literature is very rich, but I’m completely against reading it as any kind of ethnography or anthropology,” Antoon says. Rather, he is much more interested in works that challenge preconceptions, such as the false notions of Iraqi and neighbouring societies being defined by religious sectarianism, and which provide readers with alternative narratives about their and others’ societies. His own work accomplishes this in part by focusing on the traumatic effects of armed conflict on working-class civilians like Wadood, rather than on the soldiers and leaders who dominate American war literature.

“I once saw a sign outside a synagogue in New York that has stayed with me,” he recalls. “It said that when you leave this building, you can’t be the same person who entered it. That’s how I feel about works of art that move me. I want them to shake me and to remind me that, despite this horrible world, there is beautiful art. That’s something worth living for.”