Despite the ravages it has faced, the Grand Sofar Hotel remains elegant, and is finding a new life thanks to art.

Activists campaign to save the city’s iconic structures

BY ABBY SEWELL

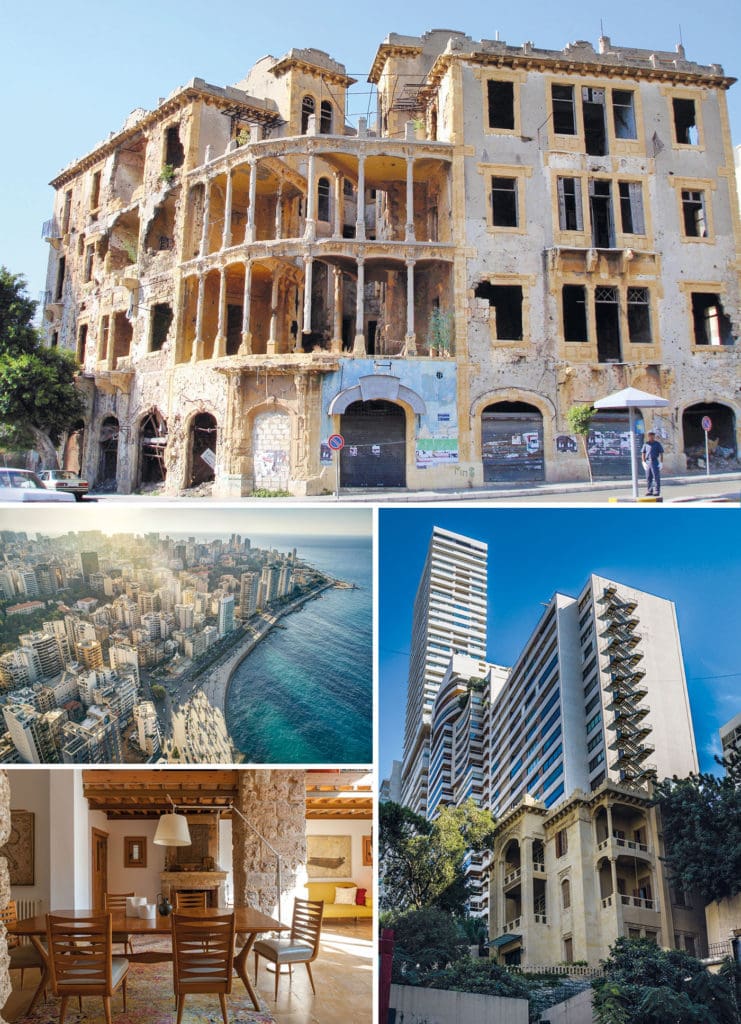

From the outside, Beirut’s Heneine Palace looks like a ruin. The wooden shutters on the windows—and the windows themselves—are broken, the walls riddled with bullet holes. The once-imposing mansion is now dwarfed by a high-rise apartment building under construction next to it. Its own fate is uncertain.

But the inside of the Ottoman-era palace, originally built for a Russian nobleman, retains much of its former glory: the crenellated arches, the ceiling decorated with elaborate geometric motifs designed in a Moorish-inspired style unusual for Beirut.

Preservation activists from groups like Save Beirut Heritage have held public events to call attention to the threatened site.

Last year, Maya Chams Ibrahimchah, a philanthropist and preservation activist who is not one of the building’s owners, took a different approach. She undertook a partial restoration of the space with her own money to throw an elaborate party for her husband’s birthday—and to prove that the space was worth saving.

Like many Lebanese, Ibrahimchah has been dismayed to see historic buildings bulldozed to make way for high-rises in the little-regulated post-war development boom.

“The destruction of the entire heritage of Lebanon is happening now as we live,” she says. “It’s very hard to deal with this, and I found that the only way of being able to preserve something or anything is to transform these palaces or homes into something that is lucrative.”

In the absence of a national preservation policy, individual initiatives like hers sometimes seem to be the only way to protect the historical buildings that have survived the wars and the privatised redevelopment of Beirut.

Gregory Buchakjian has spent the past decade photographing Beirut’s abandoned buildings in an attempt to create a sort of historical archive. He has photographed and inventoried some 760 abandoned sites, producing a PhD dissertation and an exhibition at Beirut’s Sursock Museum.

Buchakjian says that even before the civil war, which began in 1975, Beirut was not a city that took measures to preserve its historic buildings.

“This city is not a city like Rome that is a museum city,” he says. “It is a city that is completely chaotic. It’s a city that eats itself like some kind of monster, and though people are nostalgic, nostalgia is not enough to save heritage.”

But in recent years, preservation activists have succeeded in stopping the destruction of some historic sites. The most high-profile of these, formerly known as the “Yellow House” or Barakat Building, is an elegant four-story home located on the Green Line that divided east and west Beirut during the Lebanese civil war. Taken over as a snipers’ post during the war, it was slated to be demolished afterwards.

The building was saved, largely through the efforts of architect and preservation activist Mona Hallak, who has pushed for it to be turned into a “museum of memory of the city.” After undergoing renovation, the site is now run by the Beirut municipality and occasionally opened to the public for exhibitions and events.

“To me, it’s not the right way. This building has to be a museum, it’s not a gallery,” Hallak says. “But some people argue that at least it’s open to the public for some exhibitions.”

At other sites, property owners have undertaken their own renovations. One high-profile recent example is the Grand Sofar Hotel, a once-luxurious hotel and casino in the mountains above Beirut. In its heyday, it hosted luminaries and famous entertainers like the singers Sabah and Um Kalthoum and was the site of political intrigues. After the civil war began, it was abandoned, looted, and occupied by the Syrian Army.

Last year, at the initiative of owner Roderick Sursock Cochrane, the historic hotel was renovated. It hosted an exhibition of works by Lebanon-based British painter Tom Young detailing the site’s history, along with music and storytelling nights. Though it no longer functions as a hotel, it now serves once again as the site of elaborate weddings and events.

In the Gemmayze neighbourhood, home of a bustling nightlife and some of the best-preserved old residential quarters remaining in the city, Nabil Debs and his wife, Zoe, are renovating a complex of old family homes surrounding a garden into a boutique hotel.

Debs says the project was possible because his family owned the land and the properties. For those interested in buying and renovating heritage properties, however, the cost of land in Beirut is a barrier.

“Where we have our hotel, we could have a 20-story building, so if we were to buy the land, we would be buying for the right to build those 20 stories plus the potential profit,” he says. “What is difficult is that the economy is based on real estate, banks and developers, and it is unfortunate that they each feed into each other.”

Some preservation activists, including Hallak, have pushed for a national law that would create “heritage clusters” in which historical buildings would be preserved, while giving the owners rights to build instead on empty lots in non-historic areas. Different versions of a draft law have made their way to Parliament over the years but have never been actively taken up for discussion.

In the meantime, some smaller steps have been taken: a government committee must now review every request for a demolition permit in Beirut, a measure that Hallak says was “instrumental in stopping the demolition of hundreds of buildings.”

But, Hallak says, a national law is the best way to preserve Beirut’s heritage while also being fair to the owners of old buildings.

“By law, they can have a 14-floor building instead of a three-floor old house, so how do you compensate these people whose money is in their land? We are in a very small city, so land is gold.”

Joana Hammour, an organiser of the Save Beirut Heritage campaign, says even preservation activists don’t all agree on the best mechanism to protect heritage sites. But she says a national law is necessary.

“It’s not perfect, that’s for sure. There are some gaps, there are some complications, but it’s way better than the situation we’re in today,” she says. “We can’t work building by building any more. It’s really about the whole area, the neighbourhoods, the people. The law would be the umbrella for preservation of the heritage.”

Grand Sofar Hotel photograph by ANWAR AMRO/AFP/Getty Images.