A material world

UAE-based designers are pushing the boundaries of material science.

By Nicola Chilton

Photographs by Siddarth Siva

Making chairs from papyrus, leather from seed pods, lampshades from fish scales, and concrete from date seeds may sound like a school craft project, but in the UAE these fictional-sounding creations are being developed as real-world alternatives to highly polluting materials.

For Richard Wilson, founder and creative director of Colab, a Dubai-based digital materials library that supports material innovation and connects designers, architects, contractors, and manufacturers, it’s no surprise that these products have all been developed in the UAE. “This is a nation that consistently sets out to achieve the impossible and do things that others haven’t done before,” he says. “Material innovation is no exception.”

Many of these innovations are the result of the Tanween design programme run annually by consultancy Tashkeel, established in Dubai in 2008 by Sheikha Lateefa bint Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum. UAE-based emerging designers taking part in Tanween collaborate with engineers and scientists to create functional designs—furniture, lighting, storage solutions—that address the global challenge of sustainable production.

PlyPalm, a material based on the discarded branches of date palm trees, was developed by designer Lina Ghalib as part of the 2020 programme. Ghalib took inspiration from the traditional use of palm branches for arish shelters in the Gulf and furniture and bird cages in her native Egypt. Approximately 40 million date palms grow in the UAE, each shedding an average of 20 to 30 kilogrammes of waste material annually, including almost 10kg of the branch midribs that Ghalib uses.

Nuhayr Zein (Header image) Leukeather is a leather alternative made from the seed pods of leucaena leucocephala, or river tamarind. In warm shades of brown, the material has the look and feel of an exotic leather but is both sustainable and renewable. Sara Abu Farha and Khaled Shalkha (Above) Datecrete was born out of a desire to leverage a common waste material. Abu Farha and Shalkha discovered the potential for date seeds to function as a sustainable aggregate in a concrete alternative.

The result of her research in Tashkeel’s labs is a compressed hardwood-like material with structural integrity suitable for making furniture, but other products too. The branches have different tones and colours which, when combined, create a richly textured pattern. For Tanween, Ghalib developed the Yereed bench, curved PlyPalm bound by brass rods and combined with camel-leather seating. For the UAE Designer Exhibition at Dubai Design Week in November, she presented Karab, a collection of wall-mounted coat hangers in organic forms combined with brushed-brass accents.

“At the moment our products are handmade, and we ensure quality in every step of the process, doing our best not to waste material,” says Ghalib, a graduate of the American University of Sharjah. She aims to grow PlyPalm to commercial production.

Product and industrial designer Aya Moug is also taking a contemporary approach to an ancient practice, in this case using papyrus harvested from the shores of the Nile to create a versatile, plant-based biomaterial. An alternative to wood, stone and marble, the material, called Byblos and made from papyrus pulp, is organic yet strong with the potential to work in furniture production. Moug’s latest work includes the MOOY collection, an angular console and chair inspired by the Egyptian hieroglyph for water ripples.

“While papyrus is widely known as the first form of paper, it’s actually a strong and versatile plant that ancient Egyptians relied on heavily,” she says. “Today, the plant is nearing extinction, so I wanted to find a way to reintroduce it into modern life in a vibrant, colourful and purposeful form.”

There are other benefits, too. The process of transforming papyrus into a sustainable biomaterial is relatively inexpensive. The plant benefits its habitat—it filters water and purifies air. And it isn’t limited to the Nile, it can be grown around the world.

“At the moment our products are handmade, and we ensure quality in every step of the process, doing our best not to waste material.”

Lina Ghalib PlyPalm is a material based on the discarded branches of date palm trees. The result of Ghalib’s research is a compressed hardwood-like material with structural integrity suitable for making furniture.

Plants are also the foundation for Nuhayr Zein’s Leukeather, a leather alternative made from the seed pods of leucaena leucocephala, or river tamarind, a fast-growing tree native to Mexico but common throughout the tropics. Zein first came across the pods in 2020 near her parents’ home in Al Ain. “When I held them up to the sun they were translucent, with amazing colours,” she says. Her first experiments with the pods failed due to their fragility. She turned to her sister, a material scientist and engineer, for guidance and through a natural treatment process was able to create a material in warm shades of brown with a look and feel somewhere between alligator, ostrich and eel leather.

“In the beginning I wasn’t thinking of it as leather, but as a new material to be used in interiors,” she says. Made from thin, individual pods, the material didn’t have the visual consistency of leather, so Zein created modular units, cut and combined into squares to create a leather-like appearance. Each square metre of Leukeather requires 750 split pods. “At first I saw this lack of cohesion as a limitation, but then I noticed that’s the beauty of the material because every sheet is different,” she says. “Every pod lived its own life and was impacted differently by the weather. Each one of them has its own story and I love that.”

Naturally patterned, it requires neither tanning nor embossing. The carbon footprint is low, and no toxins are used in the treatment process. By contrast, processing animal hides generates thousands of litres of wastewater contaminated with pollutants like chromium and sulphides.

Aya Moug has developed a versatile, plant-based biomaterial made from papyrus pulp. The MOOY collection includes an angular console (above) and chair inspired by the Egyptian hieroglyph for water ripples. Photo courtesy of Byblos-Papyri.

Zein is now working to develop Leukeather beyond its current use in furnishings towards the fashion industry. “Once we really scale up production, we will need to have our own farm. And the more we scale up, the more carbon we offset as we plant more trees to give us the pods we need.”

Seeds are also the inspiration for Datecrete, created by wife and husband duo Sara Abu Farha and Khaled Shalkha. “Datecrete was born out of our desire to leverage a common waste material,” Abu Farha says. “Growing up in the UAE, we saw date seeds everywhere and saw how tonnes were being wasted on a daily basis, particularly from the production of seedless products like date molasses, syrup, and paste.”

The UAE produces 750,000 tonnes of dates each year, 14% of global output. Through experimentation and collaboration with local producers, Abu Farha and Shalkha discovered the potential for date seeds to function as a sustainable aggregate in a concrete alternative that has the look, feel and sheen of concrete, yet is entirely natural. “Scientific literature shows us that date seeds are similar to wood in their constituency, and that was one of the starting points that prompted our research,” says Abu Farha, an architectural engineer and urban planner who is passionate about material science. The resulting eco-friendly material maintains structural integrity without the need for cement or resin additives, with a strength that rivals concrete.

Mouldable and pourable, Abu Farha and Shalkha say Datecrete can be used wherever concrete is currently: for flooring; walkways; house footings; even furniture (the duo designed a console table for the Tanween programme in 2022). Abu Farha and Shalkha, a chemical engineer, believe that the material has the potential to be used at an industrial scale. The theory is being put to the test at Expo 2025 in Osaka from April in the form of 600 square metres of Datecrete paving for the UAE Pavilion. Abu Farha and Shalkha were also the winners of the 2024 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Award for their innovative Bee Hotel.

Alternative concrete is also a focus for Wael Al Awar, principal architect at waiwai design studio, who is working with waste brine from the desalination process.

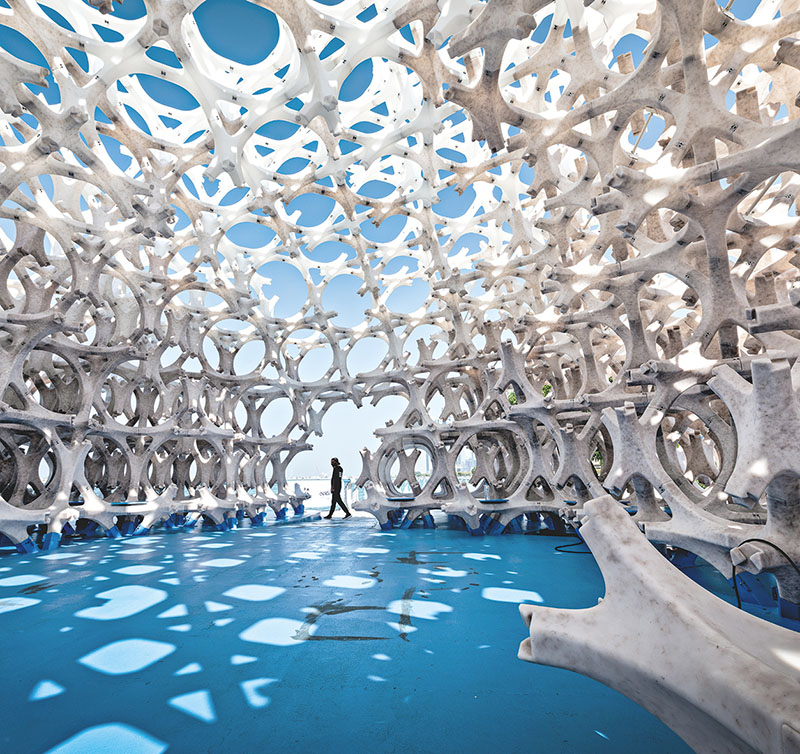

Wael Al Awar Alternative concrete is also a focus for Al Awar who is working with waste brine from the desalination process. His second prototype, Barzakh (top), was showcased at the 2024 Public Art Abu Dhabi Biennial. Barzakh photo: @ralphemerson_deperalta

Al Awar is working with Abu Dhabi’s Khalifa University to advocate for access to a steady supply of brine to scale up production of prototypes. He’s confident that given the right resources, it will be possible to make single-storey, single-family houses. “The research we have carried out shows that our approach offers a viable low-budget, low-tech and high-efficiency solution for building. Structurally, salt-based cement bricks work best in compression, not tension, which means that building multi-storey structures is more of a challenge, but this isn’t insurmountable. Traditional bricks are also a compression-based structural solution and can be used for taller buildings.”

His first large-scale iteration of the material was Wetland, the UAE Pavilion’s presentation at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale which won the Golden Lion. The second prototype, Barzakh, was recently unveiled at the 2024 Public Art Abu Dhabi Biennial. “Our local, natural material resources in the UAE are very limited, and we can’t build with wood or bamboo at any kind of scale,” Al Awar says. “The question we asked with the UAE Pavilion was whether industrial waste could be a future vernacular for architecture.”

Reducing the carbon emitted by cement production is critical to achieving climate targets. Global cement manufacturing produced 1.6 billion metric tonnes of CO2 in 2022, 8% of the world’s total CO2 emissions.

Al Awar is also researching a building material made from palm fibre and mycelium, and prototype bricks made from gum Arabic, sand, and crushed oyster shells from local oyster farms.

“A few years ago, sustainability might have been conceived as boring, but now people are aware that the creative possibilities are endless,” says Colab’s Wilson. “Materials like plastic and leather were created to serve a purpose. Now we are just aware of better options, and we all have a responsibility to explore them.”

Al Awar agrees. “What we are seeing in the UAE is more than just a trend. It’s the result of us feeling a moral obligation to respond to the climate emergency.”