An Artistic Renaissance

Contemporary Libyan art is looking back at its recent and ancient history.

By Naima Morelli

“I saw tears in people’s eyes. I saw hands on hearts,” says Libyan artist Alla Budabbus about the opening of The Libyan Pantry, a show staged in March in Tripoli’s newly restored old medina. “Libyans are still suffering from their previous experiences of war. Visitors left the exhibition with a smile. This means a lot.”

Aiming to document and preserve visual memory for future generations, the exhibition explored 70 years of Libya’s consumer culture. It presented a series of products that bore witness to society’s evolution, starting with the golden era of Libyan industry, after independence and the discovery of oil. It offered reproductions of company brands, industry logos, posters, and advertising graphics, realised by Budabbus and artist Hadia Gana.

The artworks had an interactive aspect that encouraged visitors to touch them, engaging a public beyond the usual art crowd. To the show’s curator, Najlaa Elageli, the London-based founder of Noon Arts, a platform that supports young Libyan artists internationally, it was part of the renaissance of the Libyan art scene.

“Every month I get invited to new exhibitions,” Elageli says. “People today are much more inclined to visit shows, and the old medina has a lot of spaces that are accessible to the public. There is excitement just to be able to access certain buildings. I was a bit pessimistic five years ago, but that’s definitely a positive sign.”

The art scene in Libya is flourishing after the 42-year rule of Muammar Gaddafi. “During that time artists in Libya were still creating, but most of the work had to be self-censored in order not to offend the regime,” Elageli says. While artists have gained more freedom of expression since, she says, they have only recently begun to tackle subjects such as gender and conflict with subtle critiques.

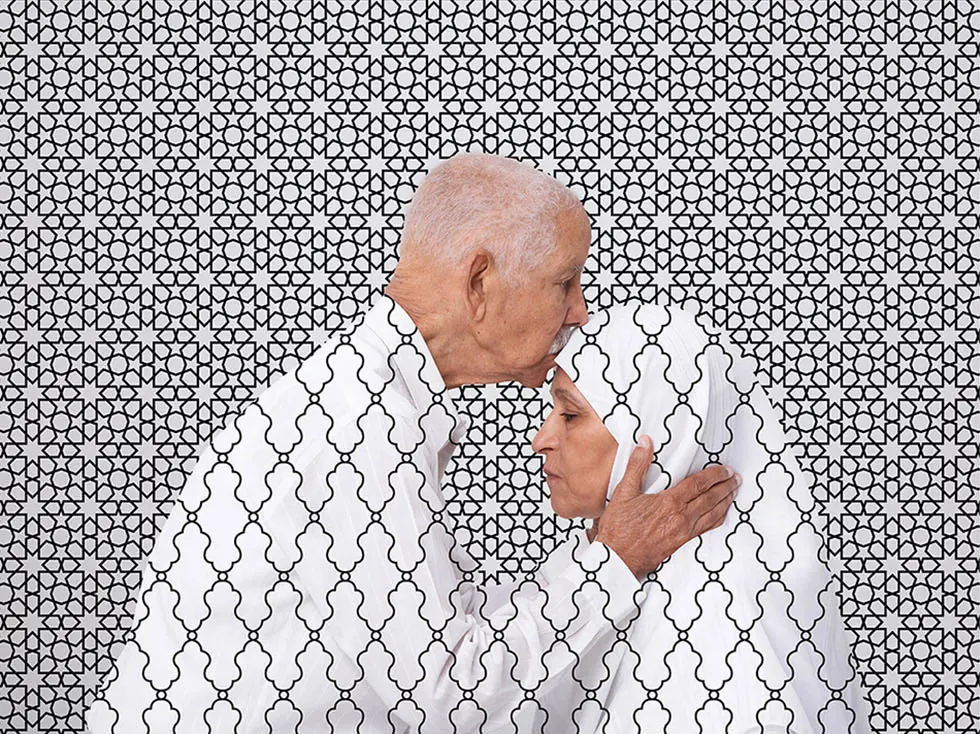

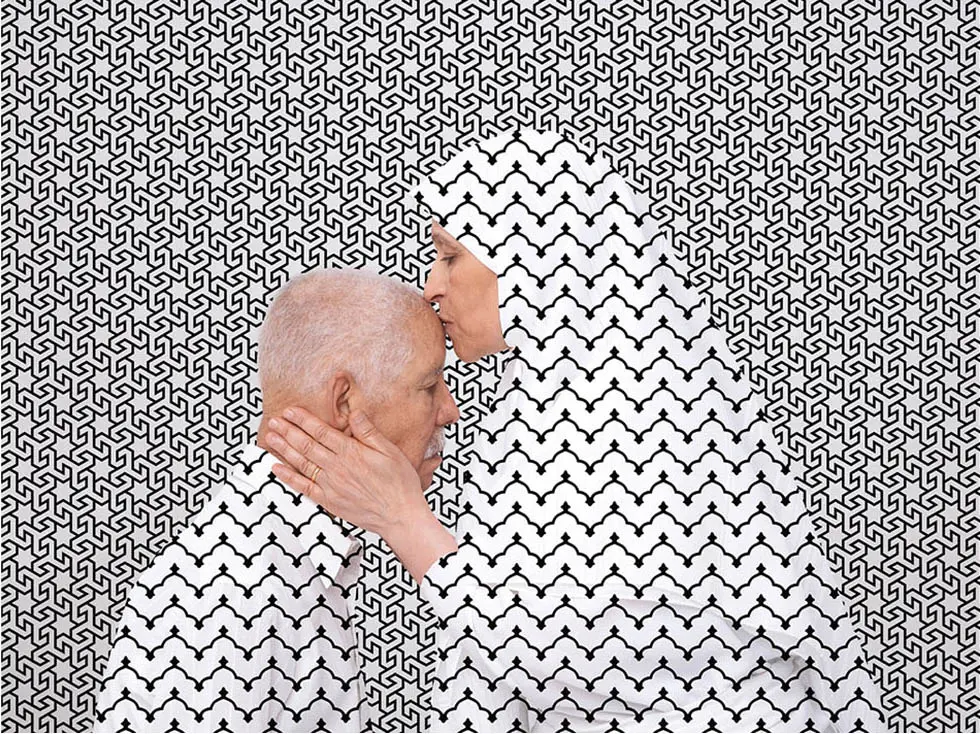

Opening image, Tewa Barnosa is part of a new generation of Libyan artists that is exploring the country’s history. Here, her installation SILENT PROTESTS. Photo by Rolf Schulten. I’M SORRY / I FORGIVE YOU (2012), above, by Arwa Abouon celebrates her parents’ union and commitment. It presents forgiveness and compassion devoid of pride or anger. Images courtesy of the Artist Estate and The Third Line, Dubai.

These themes are explored mainly by younger artists, such as Tewa Barnosa, Shefa Salem, and Malak Elghuel, who are also more experimental, employing digital tools, audio-visual installations and other media. The older generation is looking at the past 10 years in Libya in terms of society’s worries and from a historical perspective. “Most Libyan artists have been affected by the conflict, or the consequences of it in some way or another. Their work relates to it in a very original, personal, and powerful way, within their chosen medium. And yet they stand collectively as Libya’s artists,” Elageli says.

Take the installation Silent Protests by Tewa Barnosa, seen this summer in the Totalitarian Props exhibition at The Africa Centre in London, curated by Elageli and Barnosa. Past iterations of the work used calligraphy to write, on bricks, political and protest slogans originally seen on the walls of Tripoli as graffiti. The version on display in London referenced the chaos of property records in Libya, which makes it near impossible for Libyans to reclaim their house or land and be protected by law. The work echoed names written on houses around Tripoli by those trying to reclaim ownership: “It is about the written word, and how Libyans use walls to express their aspirations, delusions, and hopes,” Elageli says.

Barnosa is now recognised as one of the leading Libyan artists internationally. Involved with the Tripoli art scene since she was 17—when she founded WaraQ, an independent space in the old city—today she lives in Berlin and highlights issues peculiar to Libya through her diverse and experimental practice.

An artist of the same generation, who gained critical acclaim before her premature death in 2020, is Libyan-Canadian Arwa Abouon, whose practice was based on photography. Her most famous work, I’m Sorry / I Forgive You, captures a tender moment between her parents. It incorporates zellij, a traditional North African tile work, and has been exhibited in institutions around the world.

Museum recognition is something most Libyan artists must seek abroad, as Libya still doesn’t have a government that collects art. In fact, before 2011, Libya had few art galleries and no national museums. The only culture hub was Tripoli’s Art House, where artists staged exhibitions and foreign audiences could buy works. “As a gallery, Art House sought to shed light on the richness of Libyan art history, especially modernism, which is ignored or disregarded by most Libyans,” says Wareda Elmehdawi, its curator, who is based between Tripoli and Prague.

“The international community is hyping street art, hobbyist art, and art therapy,” Elmehdawi says. “This is very sad, as many of the modern artists have passed away in the last five to 10 years, and their work has no chance to be recognised in the near future.” Works by older artists, she says, like Bashir Hammouda, a pillar of Libyan modern art, should be treasured. Her family’s modern art collection, started by her father in the 1970s, contributes to that. “Most collectors of Libyan art [cannot] find artwork older than 1994. That’s because Art House opened in 1993, it helped treasure those artworks.”

SAHARA CHARIOT–THE GARAMANTS (2020), above, by Shefa Salem, a visual artist born and raised in Benghazi. Part of the Identity Project, the painting explores the art of early inhabitants of Libya on cave walls, valleys and desert rocks. Photo courtesy of the artist.

While private collectors are preserving the country’s art history, since 2011 it is NGOs, private foundations and embassies that foster most cultural activity in the country. A promising step in the development of the local art scene, says Elageli. Unwelcome control which distorts Libyan artistic identity, counters Elmehdawi, who argues that artists are faced with a stark choice: pursue artistic integrity or take the funding.

That isn’t the only thing dividing Libya’s art scene. The country’s two biggest cities, Tripoli and Benghazi, are ruled by different governments. While there are some well-established artists working in Benghazi, the city has been less active in terms of shows. In contrast, Tripoli’s art scene is flourishing, with exhibitions staged in an old city that has been rejuvenated by a restoration team led by Hadia Gana. One of the country’s most celebrated artists, with a ceramics and installation practice, she recently built a museum in Tripoli’s suburbs to preserve the artwork and archives of her father, artist and art researcher Ali Gana. The idea for the space was to showcase new artists alongside her father’s work, and to become a culture and education hub. Tripoli’s art scene emphasises public participation, alongside a growing number of galleries that build a market for it.

According to Benghazi native Shefa Salem—an architect and painter whose practice is rooted in socio-political issues, feminism and Libyan history—it’s getting easier to move shows from one part of the country to another. Her last exhibition travelled from Benghazi to Tripoli, and for her next solo she is looking at the south of Libya, which is too often neglected. “They don’t have an art scene, so it would be interesting to exhibit there,” she says.

Salem is deeply involved with local historical researchers, and joins trips to archaeological sites. “Maybe you’d find more information on websites and in books, but it’s important for me to get a spiritual connection with the places and our ancestors who lived there.” Information about Libya’s ancient history is sparse. “That’s when I try to use my art and imagination to fill the gaps, but it’s a difficult balance between historical adherence and my own creativity and expression,” she says. “There is a part of me that feels responsible for telling the Libya story.”

Despite the divisions that still plague the country, art represents one vehicle for uniting Libyans, forging a common ground.

“There is a strength that comes from knowing one’s history,” Elageli says. “The infrastructure might still be messy, but art is able to open new alleyways for people to understand their past, making them hopeful about the future of Libya.”