Archaeologist of the Present

Dia Mrad approaches photography like an excavation, capturing traces of history alongside contemporary artefacts that reveal a city’s metamorphosis.

By India Stoughton

Dia Mrad is known as a photographer. He is also an architect. He has recently come to think of himself as a kind of archaeologist. Mrad began his artistic career by documenting Beirut’s historic Ottoman and French-Mandate-era mansions and townhouses, immortalising their scarred beauty both before and after the deadly port explosion that tore the tiles from their roofs, twisted and snapped their ornate metal balcony rails and turned painted shutters into jagged splinters and handblown glass into deadly rain. Then came his photo series Utilities—and with it, a whole new insight into his own work.

Using his camera, Mrad excavates layers of the city’s history and creates a complex, multilayered portrait of Beirut as it exists now.

Born in 1991, Mrad grew up in the Bekaa Valley. It wasn’t until his high school years that his family moved to Beirut and he found himself faced with “this crazy amount of chaos, but also a lot of beauty.” The city came to fascinate him, first as a student studying architecture, and later as a photographer focused on its uniquely complex urban fabric.

Mrad graduated as an architect in 2017, but during his studies he had already realised that he preferred documenting buildings to designing them. In 2019, he took a job photographing properties for a real estate company. “It provided me with a unique chance to see the city from many different points of view… that you don’t normally get access to,” he says. From the balconies of homes across the city, he captured bird’s-eye views and head-on portraits of properties whose beauty could barely be glimpsed from the street.

GIBRAN KHALIL GIBRAN (2020) from The Morning After series. The day after the Beirut port explosion, Mrad captured a mural of the poet Khalil Gibran through a collapsed wall at Villa Mokbel. The image became an emblem of the city’s destruction. Opening image, AUTOPORTRAIT (2023). All images courtesy of dia mrad

Through an enormous hole in the facade at nearby Villa Mokbel, he saw a black-and-white mural of the poet Khalil Gibran—an emblem of Lebanon’s artistic and intellectual history.

Unable to source a list of buildings granted protected status by the Ministry of Culture, he began to create his own index of buildings with original historical features—and to notice how many of them were deliberately damaged by owners desperate to demolish them to make way for lucrative new towers. “I was always afraid that they were going to disappear, or something will happen to them,” he says.

He finished documenting the historic homes of Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael on July 28, 2020. Seven days later, improperly stored ammonium nitrate at Beirut’s port exploded, destroying vast swathes of the city. Mrad was out taking photographs when the blast struck. “I was thrown three metres off my scooter, along with my camera,” he says. “I left my scooter, I stood up and took some images and then started recording a video.” The next morning, he went to the affluent Sursock neighbourhood, where he had started the next stage of his photography project just six days earlier.

He saw some former colleagues, who had been setting up for a wedding at the 160-year-old Sursock Palace when the explosion occurred. They invited him inside to photograph the wreckage. Mrad’s images show antique furniture strewn across floors littered with rubble and broken glass, silhouetted against the mansion’s iconic triple-arched windows, now voids.

CISTERN VEHICLE (2023), top, from the Utilities series. Residents turned to private water companies to fill tanks and cisterns as water shortages became prevalent. Below, FULL FRAME. Prior to the port explosion, Mrad had been documenting the city’s Ottoman and French Mandate-era mansions.

Accustomed to seeking beauty in abandoned buildings, he found himself torn between horror and awe. “I remember holding back tears, becoming sweaty and irritated and not being able to make sense of what my eyes were seeing,” he says. “But at the same time, I remember feeling like this is so beautiful. Even if it’s destroyed the way that it is, you could still see the beauty of what existed.”

Through an enormous hole in the facade at nearby Villa Mokbel, he saw a black-and-white mural of the poet Khalil Gibran—an emblem of Lebanon’s artistic and intellectual history. He shot a now-iconic image of Gibran’s shadowed face, framed by collapsed masonry, and exposed rafters littered with smashed tiles. Half an hour later, the wall collapsed.

Mrad revisited all the historical buildings he had so recently photographed, showing how the explosion had flayed them in an instant, leaving only the bones. Without ever capturing a human face, he sought to convey the vast scale of the tragedy that had engulfed the city. “It’s a way of reflecting what had happened to the people living in the houses without showing injured people or bleeding,” he says. “For me, it was like the city was injured, the city is bleeding, and you could see those scars, those wounds, through the buildings.”

Mrad revisited all the historical buildings he had so recently photographed, showing how the explosion had flayed them in an instant, leaving only the bones.

GOLD IN CRISIS (2020) from The Morning After series. Maison Feghali, built in 1830, had survived the country’s brutal civil war, but was badly damaged by the port explosion. Mrad documented damaged historic buildings, fearing they would collapse and be lost.

Mrad’s photos of the blast’s aftermath were exhibited widely overseas. These exhibitions led him to a completely new project—Utilities. “People kept asking me, ‘So how’s the situation in Lebanon? What is happening now in Lebanon?’” he says. He realised he couldn’t explain it, even to himself. “I started asking myself, ‘What is really happening in Lebanon? How are we living? How are we surviving? What is our day-to-day life like?’”

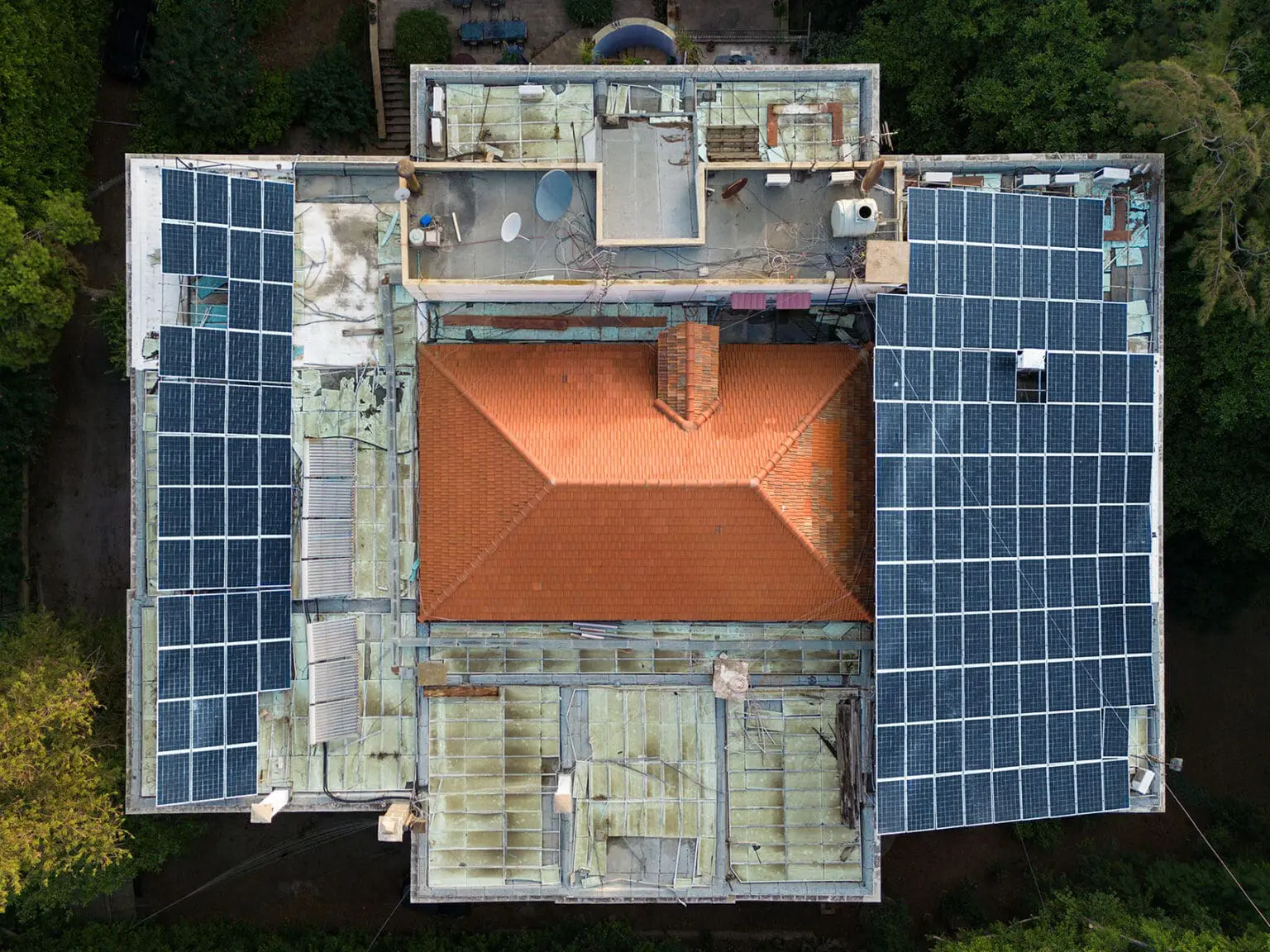

Returning to the streets, he looked for physical changes to the urban fabric that showed how the economic crisis was affecting people. He focused on three things: electricity cuts, reflected in the sudden proliferation of solar panels on rooftops; water shortages, glimpsed in the tankers and containers trucked across the city daily; and the banking crisis, revealed through the armour-like adaptations made to banks and ATMs to prevent people deprived of their savings from trying to take their money back by force.

It was around this time that Mrad began to see himself as a kind of archaeologist of the present. He saw the city as a stone and concrete palimpsest, telling a story in chapters that, to the discerning eye, can be read all at the same time.

“If you think of the civil war, that left a layer of damage and destruction,” he reflects. “The explosion did its own layer. Even if you think of the revolution, it added a layer into the city, which was the damages caused by the mini riots or the graffiti that was everywhere. So there’s always something tangible that you’re able to notice within the built environment that gives you clues to what is happening in the city. That’s something that I hadn’t really realised until I started Utilities.”

SOLAR TABLET II (2023) Mrad’s Utilities series documented Lebanon’s economic collapse. The failure of state services and the lack of basic utilities meant many turned to private solutions. Solar panels offer an alternative to a failed electricity grid.

To capture the rooftops, he used drones. Carefully composed and beautifully balanced, his aerial shots have a simple surface geometry that belies their details. Shiny solar panels now sit alongside century-old stonework, illustrating the swift changes forced by urgent necessity. The project was picked up by the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, where Mrad will showcase the photographs in a large installation this November.

“Their theme is the beauty of impermanence, so it focuses on solutions that are created out of conditions of scarcity, which is why they thought this project fits in perfectly, because it is an individual solution born out of a lack of power,” he says—a statement heavy with dual meaning.

Mrad is deploying his methodology outside Beirut for the first time. This year, he undertook two three-month-long international residencies. In Riyadh, “I started to realise how I can connect it more with my practice that looks at the transformations in the built environment and the narratives that are embedded within the materiality of the city,” he says. In Paris, he focused on the long history of architectural exchange between France and Lebanon and how it is reflected in the urban fabric.

He plans to take his unique excavation method further. “Instead of looking at the building as a whole, I’m looking at the elements that make up the built environment, so like the process of extraction, but also what happens to buildings when they die?”

His next project is rooted in the relationship between Beirut and its inhabitants, asking questions about history, metamorphosis and legacy. “For me,” he says, “memory is kind of embedded within the material, within the physical. When it turns to dust, what happens to the memory—where does it go?”