Heritage comes Home

Ravaged by decades of conflict, Iraq’s rich history was looted and sold abroad. But the country is now hunting down its stolen heritage.

By Rebecca Anne Proctor

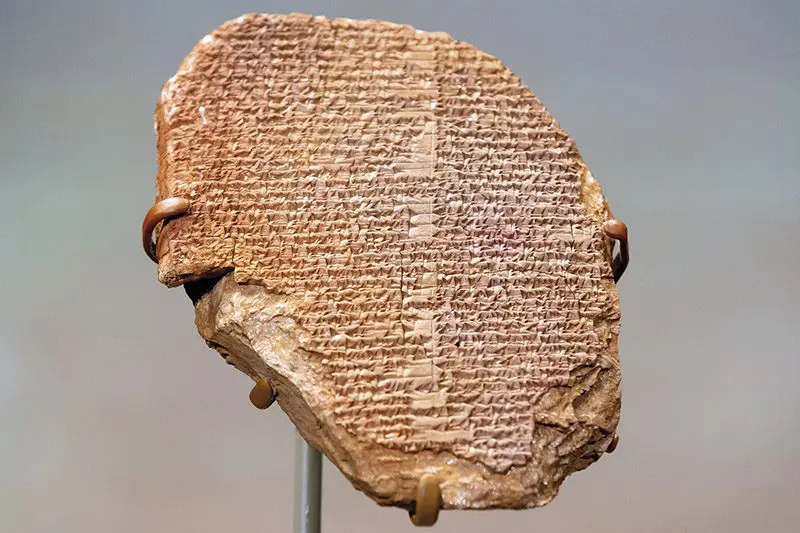

It could easily be mistaken for a lump of dried mud. However, the brick of clay and straw is a 2,800-year-old tablet of cuneiform script—one of the earliest forms of writing dating from the Babylonian era. It refers to the construction of a ziggurat (a pyramidal temple) and includes the insignia of Shalmaneser III, the Assyrian king who ruled the Nimrud region—what today is northern Iraq—from 858 to 824 BCE. Somehow, the tablet turned up in Italy in the 1980s.

The precious tablet was returned to Iraq last June, one victory in a broad campaign to recoup the country’s stolen antiquities. Present-day Iraq was home to the earliest known human civilisations. Mesopotamia—Greek for “between rivers”, namely the Tigris and Euphrates—stretched across most of Iraq to eastern Syria and southeastern Turkey and was home to the Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians, civilisations that built vast empires and great cities.

Rich with relics of this long history, the region has always attracted explorers, archaeologists, and looters, but the thefts reached crisis level amid the chaos of the US-led invasion of Iraq 21 years ago. From the 7th to the 12th of April 2003, the collection of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad was ransacked. The national museum remained shuttered for almost 12 years.

In the opening image, Muhsin Hasan, deputy director of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, sits amid destroyed artefacts at the national museum. In the days prior to this image being taken, on April 13, 2003, the museum’s collection had been ransacked. Above, Mosul Cultural Museum was inaugurated in 1952 by King Faisal II to tell the story of northern Iraq. In 2014, it was bombed and plundered by ISIS, its treasures looted or destroyed. Below, the Gilgamesh Dream Tablet—which dates back 3,500 years and is one of the world’s oldest surviving works of literature—was returned to Iraq in 2021. Top photograph of Muhsin Hasan by Mario Tama / Getty Images; Museum: courtesy of Mosul Cultural Museum ; Tablet: Michael Reynolds / EPA-EFE.

Part of the country’s mission to rebuild involves recovering from abroad its looted cultural property. To do so, it has called on international cooperation.

“We have witnessed the biggest recovery of Iraqi artefacts over the last [three] years,” says Dr. Laith Hussein, director of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage. “Every day we are receiving more and more pieces from countries around the world.”

In August 2021, 17,000 Iraqi artefacts held by the retailer Hobby Lobby and Cornell University in the US were repatriated.

Two months later, Iraq recouped the Gilgamesh Dream tablet, a small clay tablet dating back 3,500 years and bearing a portion of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an ancient Mesopotamian saga recorded in the Akkadian language about the heroic king of the city-state of Uruk. Looted from an Iraqi museum during the Gulf War, it was smuggled through many countries before ending up in Hobby Lobby’s Museum of the Bible in Washington, where it was seized by US authorities. It was, according to Iraq’s foreign minister, one of 17,926 artefacts recovered from the US, UK, Italy, Japan and the Netherlands that year.

In February 2022, a private museum in Lebanon returned more than 300 ancient cuneiform writing tablets. Today, the Gilga- mesh Dream tablet is on display at the Iraq Museum with a plaque explaining its significance and its repatriation.

“The tablet was received in Baghdad as if it was a national hero,” says Katharyn Hanson, head of research at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum Conservation Institute. “This ancient clay fragment is a national treasure in Iraq. Each artefact that returns to its rightful place of origin helps mend some of the rips in the fabric of identity. Obviously, this mending isn’t the same as to have never suffered the injury in the first place, but if we can assist with some mending, I think we are doing a service to the future of cultural heritage.”

“These artefacts symbolise the strength of ancient heritage. Unfortunately, they have been looted and destroyed for terrorist financing.”

Top, staff at Iraq’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs work around crates of looted Iraqi antiquities returned by the US, ahead of a handover ceremony on August 3, 2021. Above, stone tablets, among the thousands of artefacts Iraq has recovered from around the world. Top photo: Sabah Arar / Getty Images; Tablets: Trustees of the British Museum.

In 2019, the British Museum returned 156 Mesopotamian texts in cuneiform script written on clay to the Iraq Museum. The largest haul of looted items to be found in the UK and returned to Iraq, they were seized as part of an operation by the British Government’s Fraud Investigation Service. Mostly economic documents, letters and legal texts, the tablets range in date from the third millennium BCE to the fourth century BCE and were created in the lost city of Irisagrig. The city’s existence became known only when tablets mentioning it were seized at the Jordanian border in 2003.

Last May, the US handed back two sculptures, a Sumerian alabaster bull and a Mesopotamian limestone elephant from the ancient city of Uruk (modern day Warka). The items, looted during the Gulf War and smuggled to New York in the late 1990s, were seized from private individuals.

“These artefacts symbolise the strength of ancient heritage,” Dr. Hussein says. “Unfortunately, they have been looted and destroyed for terrorist financing. In the process of smuggling these pieces huge damage has been caused to our cultural heritage. We have lost many important pieces, like those that were once in the Mosul Cultural Museum.”

One of the country’s most important mu- seums, it was inaugurated in March 1952 by King Faisal II to tell the story of northern Iraq. Iraqi architect Mohamed Makiya married elegant modernism with inspiration from the Assyrian civilisation whose last capital, Nineveh, is across the Tigris River from Mosul. The museum was bombed and plundered by ISIS when it took over Mosul in 2014. Its treasures were looted or destroyed, including two Lamassu guardian figures—winged bulls with human heads—and thousands of rare books and manuscripts were burned. Precious Assyrian monuments at the nearby archaeological site of the ancient city of Nimrud were damaged or razed, including the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II and a 2900-year-old ziggurat.

Top, the mask of Warka dates back to 3100 BCE. Looted from the Iraq Museum in April 2003, it was later found in an orchard north of the city. Above, a limestone head depicting King Sargon II, an eighth century BCE Assyrian ruler, is one of the cultural treasures illegally smuggled into the US that has been returned to Iraq. Mask photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin; King Sargon II: Kelly Lowery / U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“ISIS was trying to destroy the historical memory of the Iraqi people,” says Zaid Ghazi Saadallah, the museum’s director.

But now the museum is coming back to life. Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, part of the Ministry of Culture, is overseeing the museum’s restoration with support from the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas, the Musée du Louvre, the Smithsonian Institution, and the World Monuments Fund.

It recently entered the second phase of its rehabilitation. After a painstaking effort to catalogue what is missing and restore those that remain, focus has shifted to the building itself. The museum is set to reopen in 2026. But not all the damage will be undone. In the Assyrian Hall a crater gapes in the floor, the result of an ISIS explosion. Mosulites were asked how the hole should be treated—covered or left as a scar. They chose the latter.

While there has been an increase in the return of artefacts, there is much to do. “There has been progress, but at a frustratingly slow pace,” says the Smithsonian’s Hanson. Investigators in Baghdad and law enforcement around the world “have been working diligently to recover and repatriate lost Iraqi artefacts, but many are still missing.”

They are being hunted on the black market and in auction houses, where identification papers are often forged. Iraq has signed up to global agreements, including UNESCO’s 1970 Convention, ratified by more than 140 countries, which seek to prevent the illicit trade in cultural property. But the challenge is often proving the state of origin. If the artefacts are numbered, as museum pieces typically are, it’s easier. Harder are pieces stolen from archaeological sites—and Iraq has over a thousand of those.

In March 2023, Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum in Atlanta returned a Nimrud ivory. It was likely part of an inlay in palace furniture from Fort Shalmaneser (part of ancient Nimrud) and dates to the 7th century BCE. Looted from the Iraq Museum in 2003, it was sold to the Carlos Museum with false papers in 2006. A tip to the US Federal Bureau of Investigations led to the repatriation.

The returns have shone a light on the thriving market in looted antiquities and demonstrated the effort of countries, UNESCO, and others to curb the illicit trade in ancient artefacts and to repatriate those stolen.

Seated at his desk in the Iraq Museum, Dr. Hussein is determined to find more. Iraqi heritage, he says, “is important to the world.” He lists the many countries and organisations that are helping Iraq to recover its looted history. When the pieces are returned, he says, they are displayed in Iraq’s museums, “where they belong.”