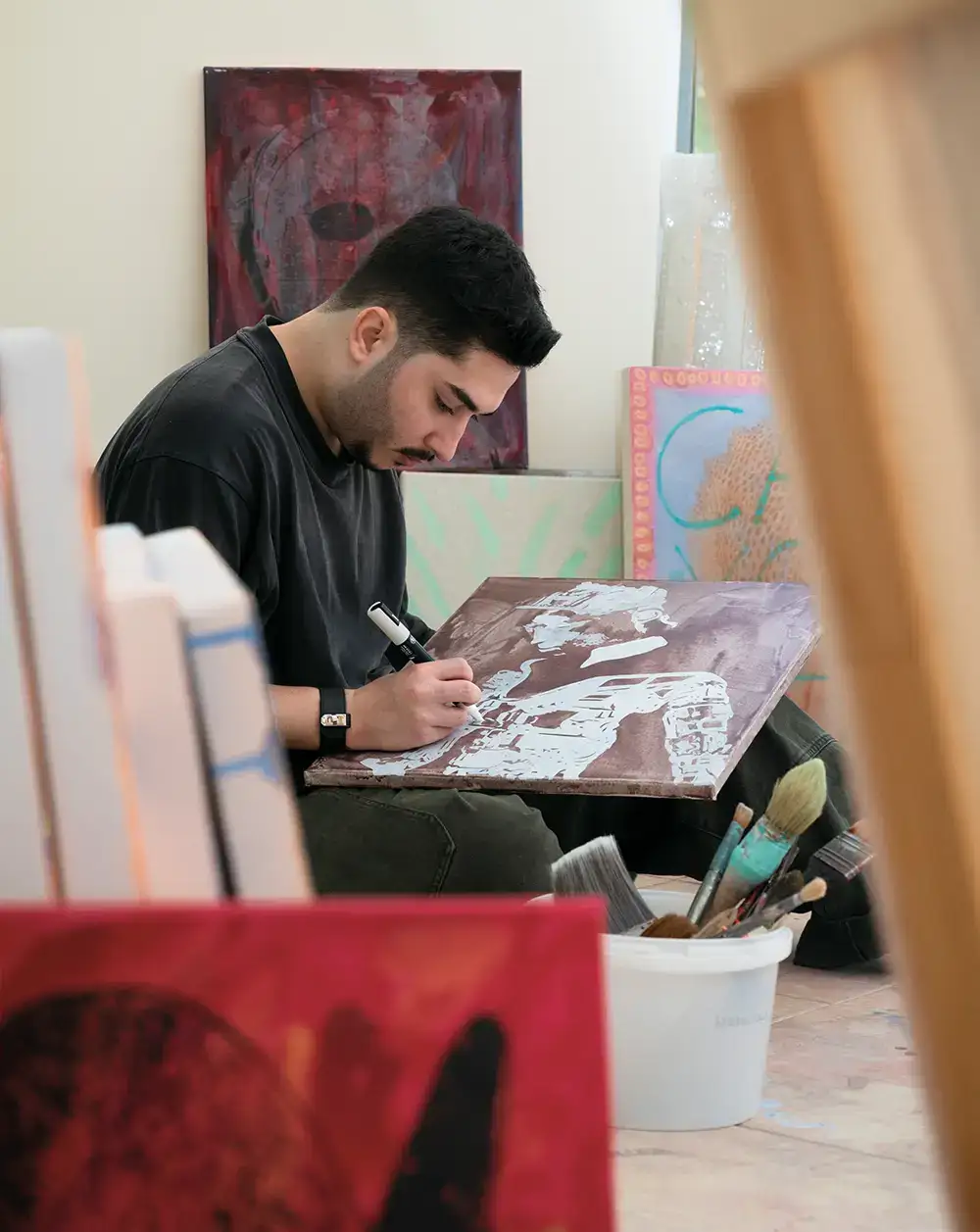

In the studio

with Talal and Ziad Al Najjar

The brothers share a passion andan eclectic studio, but their practices and outlooks are very different.

By Rahel Aima

PHOTOS BY BENJAMIN MALICK

Entering Talal and Ziad Al Najjar’s studio feels like walking onto the set of a 1990s slacker movie. In the Emirati brothers’ shared apartment-turned-workspace, the main room is filled with Ziad’s large, inscrutable canvases. The bedroom is a hangout space, with smaller paintings and sculptures by Talal. Here, the Dalai Lama is pinned up next to a poster of the David Cronenberg twin thriller Dead Ringers. A TV rests on a console overflowing with books that run the gamut from Bauhaus and Marxist philosopher Bifo to Islamic architecture, formaldehyde photography and medieval bestiaries. A stack of PS4 games shares space with a Diptyque room spray and a 3D-printed statuette of Talal in a goblin mask.

“I’m messier than Ziad and I like stuff more than Ziad. When I work, I like having random things around,” Talal explains as we sit on the powder-blue couch. “When I was a kid, I was obsessed with costumes. I want to start making videos where I do more performative stuff, playing these characters or something.”

“We can make masks,” offers Ziad, who has been experimenting with using latex and tattoo guns in his canvases, which intimate both human ribcages and spiny, spotty nudibranch roadkill. “There’s just something about working on fabric, stretched or not, and thinking directly on this material,” he explains, “regardless of whether it’s painting or not.”

Talal Al Najjar’s practice incorporates sculpture, video, sound, CGI animation, painting and installation, in addition to writing and curation. He is interested in history and anthropology, often fusing different temporalities in the same piece.

Talal, for his part, has put painting aside to play with 3D printing, and plot out Harmony Korine-style video works in advance of a solo show at Tabari Artspace in Dubai this autumn. He’s particularly interested in trickster archetypes and closing the distance between the European folkloric figure of a goblin and their pre-Islamic peninsular analogue, the ghul or ghulah. “I think it’s cool because it’s this punky figure, this gambling trickster character that’s untrustworthy, but also funny, unserious.”

With their multicultural backgrounds—an Emirati architect father and a Puerto Rican artist mother—the brothers are adept at bridging cultures. They finish each other’s sentences and are routinely mistaken for twins, although Talal is two years older. Ziad explains, “I think it’s also because we’re very close. We tend to be with each other a lot of the time.” They grew up in Sheikh Rashid Tower—Dubai’s first high-rise and a 1970s icon—before moving to an Al Barsha villa their dad designed. They attended the elite Rashid School for Boys, with summers spent visiting family in the US.

Ziad reminisces about the daily commute to school in the Nad Al Sheba community of Dubai. “It was very green. I remember palm trees, and grass; it was always lush and very long.” Unsurprisingly for an artist known for drawing from nature, he is equally rhapsodic about the rippling golden fields of his grandparents’ 1880s homestead in Plankinton, South Dakota (pop: 781). “That sounds like a horror movie, but it was so charming. It always made me think of Radiator Springs from the Cars movie. It’s flat, extremely open, all cornfields. It was peaceful. I remember thinking ‘wow, we can be here a week but it feels like a month, in a nice way.’”

Top, Symbiotic: Hyperreal, NYUAD, Abu Dhabi (2023). Above, Tuwatam (Jalis) (2020). Talal’s works veer towards body horror. Even as figuration has remained central in his practice, he is increasingly interested in the animal body. Symbiotic courtesy of the artist; Tuwatam courtesy of The Mestelan Collection.

The Al Najjars’ childhood was one filled with art, from after-school crafts with their mother to classes and summer camps. Especially formative was a month-long intensive camp in Long Island, New York, when the brothers were 6 and 8. Years later, their mother would recount a story about a Monet-esque haystack painting Ziad had made at camp: an older couple she met on a train tried to buy it and were surprised to learn it was made by her young son. “I’m just there, probably feet not even touching the floor. We still have that painting,” Ziad laughs. Their father, who was immersed in Dubai’s 2000s cultural scene, designing spaces like the seminal concept store Fivegreen, was equally supportive: Talal describes his comprehensive knowledge of art history and contemporary art.

Growing up with mixed heritage wasn’t always easy, especially in those early post-9/11 years. Despite speaking the local dialect, fellow students would speak to them in English. “A lot of them were Bedouin folks, which is not us. And then there were kids like us who were like, American mom… I had a kid call me George Bush when I was in Grade 1,” Talal remembers. Ziad adds that despite their identity crisis, the diversity of their experiences is reflected in their practices. “We tend to just make with very few constraints which I think is good because otherwise we would be a little too beige. A little bit too familiar in what the work portrays, either conceptually or representationally.”

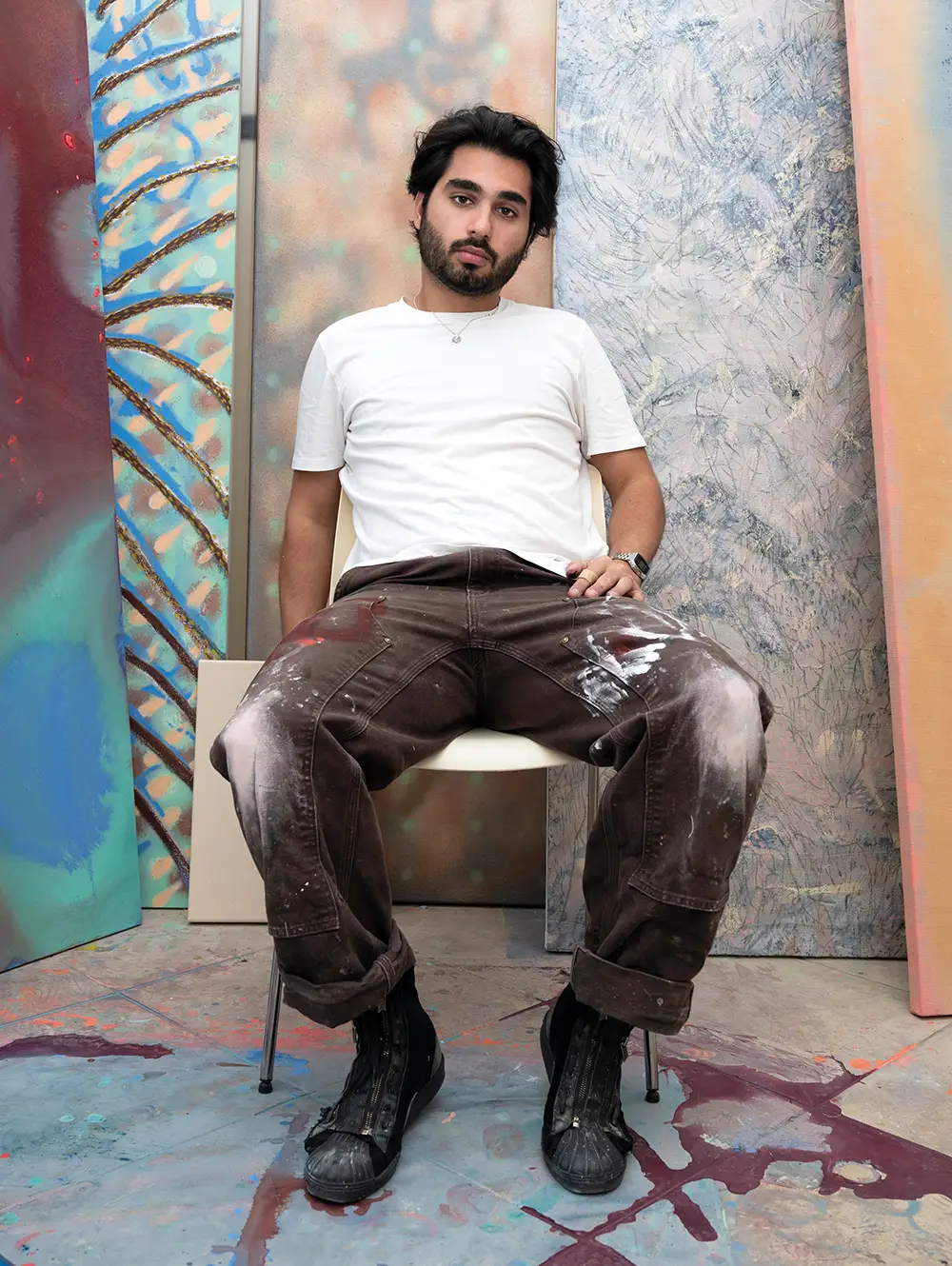

Top, Untitled (Ameba 2) (2022). Acrylic, pastel and mixed media on raw canvas. Above, Ziad Al Najjar. Artwork courtesy of the artist.

From an early age, Talal wanted to make art and exhibited for the first time at 16, at Sikka Art Fair in Dubai. Feeling suffocated by the primarily nationalistic art prevalent at the time, he moved to the US to do a BFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Ziad joined him two years later, albeit via a different route. He had been playing semi-professional football and considered going pro, but with his grades slipping realised an academic degree was more important. Undecided between art and architecture, receiving a merit scholarship from SAIC—plus Talal’s presence—made the decision easy. Talal later earned his MFA from the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena.

Noting the Diptyque again, I ask how they would distil their practices down to a smell. Ziad muses it would be cut grass or the anosmia of outer space. Talal settles on ammonia and melted plastic. Our conversation is wide-ranging, spanning DNA tests, evolutionary theory, and the history of the Arabic language, before coming back around to their studio practices.

“I really value the time I have in my studio, because my work is very labour intensive, especially with the mark making. It takes time and a lot of thinking to work through ideas, work through technical issues,” Ziad says. Over time, his saturated, high-contrast palette has become softer and more diluted. A 2023 duo show with Talal at the NYUAD Gallery was a turning point. He presented unstretched paintings, overlaid with tone-on-tone mark making, that wholly resisted documentation. “Those things are invisible, they’re just glowing. You can’t see the representation of the figures or animals or landscapes or the mark making, and I loved that the work was able to trick technology.”

Figuration has reigned in the last year, with a move towards elongated, Slenderman proportions. “It’s a way of reflecting existentially on my own physicality, the way we move.” He describes his painting process as meditative and deeply embodied, adding that “compositionally, there’s something that’s spiritual, that’s very symmetrical. There’s usually this bursting from inner to outer: I’m thinking of them jumping out, jumping in.”

An inveterate reader and YouTube wormholer, Talal is especially interested in history and anthropology, often frankensteining together different temporalities in the same piece. He incorporates imagery from Saudi and Sharjah archaeological digs, as well as the ancient Elamite dynasty of southwestern Iran. Ziad, in turn, tends to draw from art history, particularly miniatures and global vernaculars, but adds that the body as a subject transcends both time and notions of contemporaneity.

Yet if Ziad’s works are body conscious, Talal’s veer towards body horror, which he says “confronts you with that viscerality of existing, of your mortality.” His references tend more theoretical, more online, which becomes most overt in his writing and curatorial practices. The writings of Hito Steyerl and JG Ballard, and above all, the violence of modernity, loom large. Even as figuration has remained central in his practice, he is increasingly interested in the animal body, from lizards to dogs with prosthetics and the co-evolution of animals and humans.