Keeper of memories

Journalist-turned-novelist Feurat Alani bears witness to a city, and a country, that no longer exist.

By Marcia Lynx Qualey

In the summer of 2016, as Iraqi and US forces advanced on the ISIS stronghold in Fallujah, Iraqi-French journalist Feurat Alani watched as self-proclaimed experts spread across social media. These commenters portrayed Iraq as a place without history or cuisine, without families or holidays. The country they described, he says, was a place without ordinary joys—it had only darkness and violence.

Indeed, since the 2003 US-led invasion, from which the country has reeled for two decades, readers around the world have been overwhelmed by grim caricatures of Iraq, most often told from Western perspectives. The city where Alani’s father grew up, Fallujah, became a bogeyman, as though it were not a city with its own long story, but a creature that snatched away children in the night.

Alani says there were so many “so-called experts—who most of the time had never been to Iraq, had not even read anything about Iraq—that I felt I had to, in my small way, bring readers something different.”

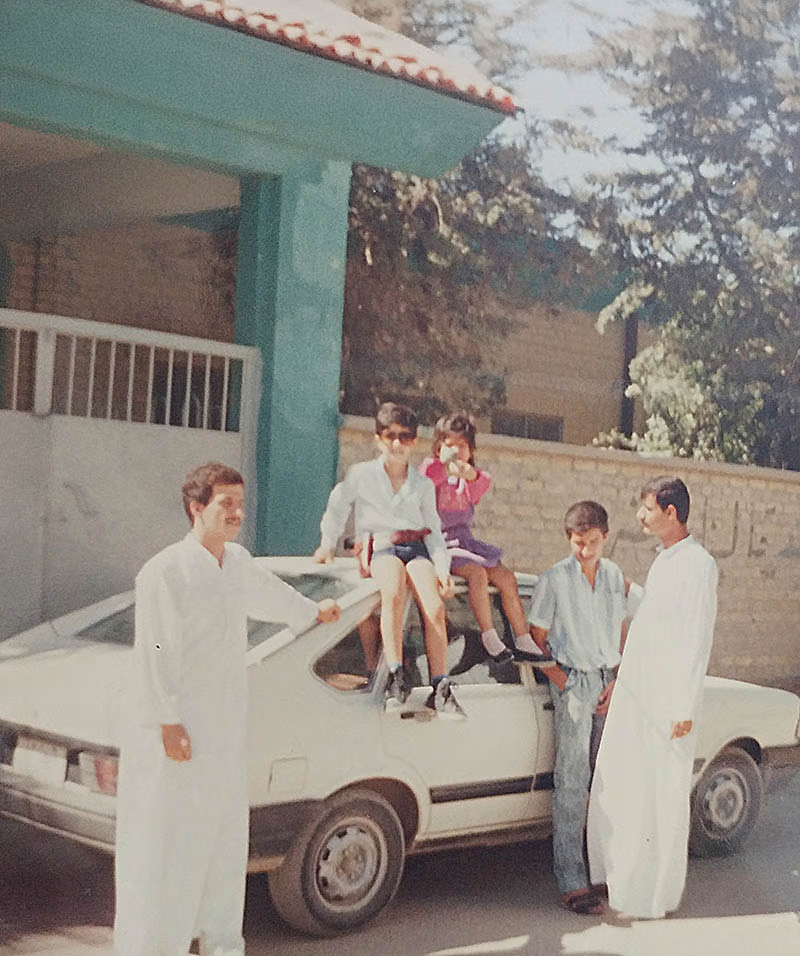

Feurat Alani grew up in France. But it was a childhood visit to meet his family in Iraq that set the course of his life. Courtesy of Feurat Alani.

At first, Alani hadn’t expected this “something different” to become a book. He had intended to share his experiences only on Twitter, to counterbalance the erasure of Iraq as a real place that was home to real people. That summer of 2016, he sat every day at his laptop and wrote 10, 20, or sometimes 30 short observations. He would then thread them together on Twitter, with no plan except to tell his story chronologically, beginning with the first time he had gone to visit family in Baghdad and Fallujah.

He not only told the story of the best kebab restaurant in Fallujah and the “best ice cream of my entire life,” which he found in Baghdad, but also of the sharp class differences between his Baghdad and Fallujah relatives. He went on to describe the challenges of his time as a young journalist in Iraq, covering the country for the French press.

At some point that summer, he says, “I realised I had reached more than a thousand tweets.”

Alani then began a year and a half of work with illustrator Léonard Cohen, which produced both a graphic novel based on the tweets, and an animated film of the same name: Le Parfum d’Irak, released in 2018. The following year, Alani was awarded the Albert Londres Prize for the work, the most prestigious award in French journalism.

Both the illustrated memoir (now translated by Kendra Boileau as The Flavors of Iraq: Impressions of My Vanished Homeland) and his 2023 debut novel, Je me souviens de Falloujah (now translated by Adriana Hunter as I Remember Fallujah) are released in English this year.

This marks a considerable enrichment of Iraqi literature available in English. While tens of thousands of Iraq-focused books have landed in US and UK bookshops since 2003, very few were written by Iraqis. This is particularly true when it comes to stories about Fallujah. Publishers have brought out dozens of accounts by US soldiers and a few by US and European journalists.

Alani, too, is a journalist who grew up in France. He was born in Paris, where he knew few Iraqis. But it was his first visit to meet his family in Iraq, when he was eight, that set the course of his life. Upon his return to France, Alani had to tell the tale of his two-month trip to his teachers and schoolmates, for whom Iraq was something strange and unknown. He has been translating Iraq for new audiences ever since.

The Flavors of Iraq, built from his tweets in the summer of 2016, is just that sort of patient explanation. The tweets are an oddly perfect fit for a graphic novel. Each compact bit of text is like a panel, with the comic’s “gutters” in between, which leave the reader to fill in the connective tissue. Alani’s tweets are fleshed out with footnotes that go into greater depth on important historical moments. They are accompanied by Cohen’s haunting, almost dystopian drawings, which sometimes feel like posters hung on a wall, glaring down at you.

Soon after the release of his illustrated memoir and film, Alani’s father developed cancer and died in 2019. The author had planned to write about his father—a dissident who had fled Iraq after being imprisoned by Saddam Hussein—but, “In our real life, when I was questioning him, I didn’t get any proper answers.”

Without the material to build a work of nonfiction, Alani shifted to fiction. Although the novel I Remember Fallujah is not about his father, it is built around a father-son relationship. The book’s core drive is to discover the father’s true identity, and the urgency is that this must be done before the father loses his grip on his memories, and then on his life.

The novel takes place in multiple timelines: the 1950s and ’60s in Fallujah and Baghdad, when the narrator’s father is growing up; the 1980s and ’90s, when the narrator himself visits Iraq from France; and then in 2019, when the father is dying, and the son must unravel the mysteries of his identity before this window closes forever.

Writing a novel was much harder than crafting a memoir, Alani says, “because I’m a journalist, and I’m really attached to details and to the truth.” He spent months staring at a blank screen before he could let go of the idea of telling a literal truth, allowing himself the freedom to invent.

The result is a rich portrait of a father-son relationship across countries and time. In I Remember Fallujah, the father is tight-lipped about his past and sometimes violent, as in one incident where he memorably head-butts a stranger on a train. But he’s also willing to do difficult things to support his family, risking imprisonment in France as he sells postcards to tourists without a permit, as he once faced risks to make Iraq a better place.

Yet some of the most compelling aspects of the novel are neither about Iraq nor France, but about the nature of remembrance. The book has a number of interesting observations about memory, which, the narrator says, “holds on just as readily to both what it wants and what it can’t abide.” The story is grounded in the son’s hunger to make these recollected fragments of his father’s life into a story, whether it is all strictly true or not.

Feurat Alani has, in both these books, created a shared imaginary space in which the reader who has never been to Iraq can step inside. We get to know his family, explore Fallujah and Baghdad, and live life as an Iraqi immigrant in Paris. These two books enlarge the space in which Iraq is not a caricature but is rather a real place of family rivalries and class divisions; of love and practical jokes; of tenderness and of loss.