Looking For Ghosts

The death of a young singer might drive its plot, but Said Khatibi’s new novel is about the disappearance of many people, and coming face to face with the past.

By Marcia Lynx Qualey

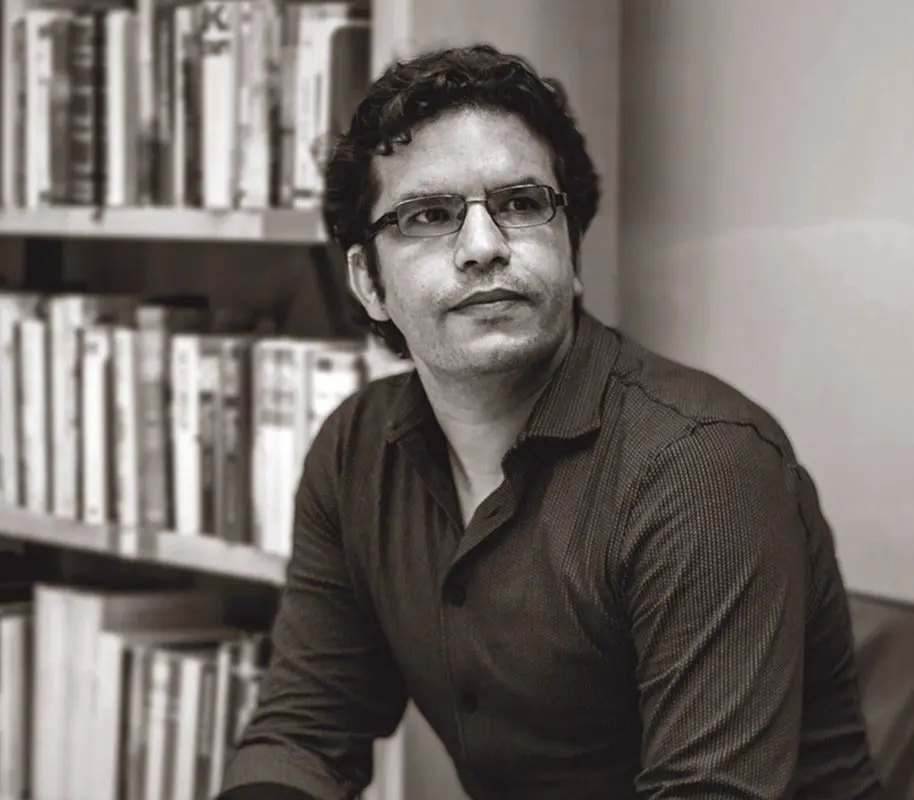

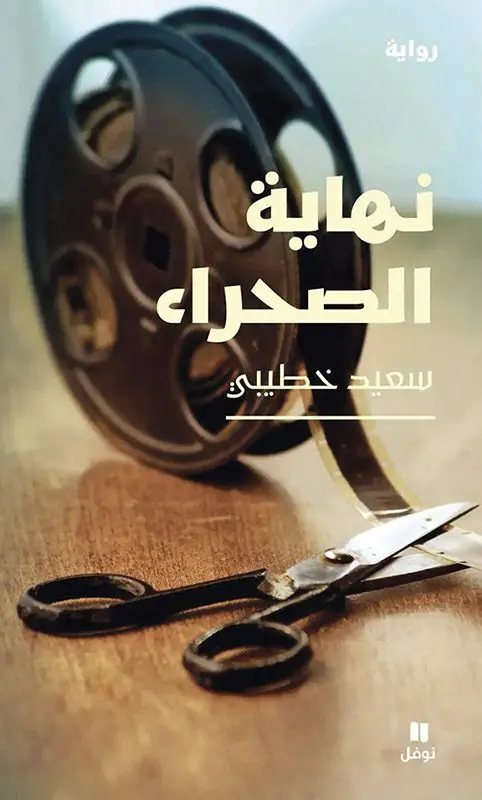

Said Khatibi was three years old in the autumn of 1988, when the events in his latest novel take place. His literary murder mystery, The End of the Sahara, is mostly set in the central Algerian city of Bou Saada, where he was raised, in the days leading up to the country’s deadly October riots.

It’s easy to imagine a young Khatibi toddling around the novel’s Trabando Market, holding onto his mother’s hand as he gazes curiously at the characters in his novel. Perhaps he passes the attractive young singer Zakia Zaghouani, or Zaza, in the days before her murder, or the incompetent and greedy Inspector Hamid, or the sardonic and mishap-prone Ibrahim, who runs a local video-rental store until his entanglement with police.

Many of the city’s residents take the stage in this polyphonic murder mystery, which investigates not only Zakia’s murder, but many other disappearances and betrayals. It isn’t a traditional, plot-driven detective novel, in the mould of Algerian writer Yasmina Khadra’s Inspector Llob series. Khatibi’s Inspector Hamid is just one of the richly drawn point-of-view characters investigating Zakia’s murder. And among all the characters we hear from, he is perhaps least likely to find the murderer. He is not only corrupt and incompetent, but also jealous of anyone who had ties to the singer, and far more interested in convicting Zakia’s fiancé than in finding any actual killers.

On their own, none of Khatibi’s characters could help us see and solve the murder. For that, we need a mosaic of many voices: Noura, the lawyer who represents Zakia’s fiancé; Ibrahim, who runs the VHS rental shop and whose mother is a cleaning lady at the hotel where Zakia worked; Kamal, the front-desk clerk at the hotel; Maimoun, the hotel’s owner; the Golden Sheikha, a rival singer; Zakia’s fiancé, Bashir; and more. Most of them are searching not just for Zakia’s killer, but for the stories of other ghosts flitting through the city.

Indeed, when Khatibi talks about the setting of his fourth novel, winner of a 2023 Sheikh Zayed Book Award, he describes a city filled with ghosts: the ghosts of abused and murdered women; the ghosts of fathers who died during the country’s war for independence; and the ghosts of Algeria’s long colonial period.

Whether or not people want to hear about it, Khatibi is determined to explore his country’s past: as a journalist, as a translator, and as a novelist.

The novel takes place a generation after the country’s 1954-1962 independence war, but that war is never far from the characters’ minds. Ibrahim spends the novel searching for information about his father, who disappeared after the war. Khatibi says there were many disappearances in his native Bou Saada. In the 1960s, Jewish and Christian communities were forced to convert or leave. In the 1980s, when the novel is set, women began to disappear from public life. Then, in the mid-1980s, the country was given a huge shock when the price of oil abruptly fell.

“The television news started saying that we’re going to live in difficult times,” Khatibi says. “People were panicking. Then France required visas for Algerians, and Algeria did the same. The number of tourists dropped. We were stuck inside the country. Then the shortages came. There was nothing left in the stores: no sugar, no butter, no medicine. The government no longer had the money to import necessary products.”

It is in this atmosphere of anxiety and deprivation that Zakia is murdered. The reader must consider many suspects, as many of the characters had a motive to kill the pretty young singer: her brothers, who didn’t approve of her independence; her obsessive and violent previous fiancé; her boss, who wanted to marry her; or even Inspector Hamid himself. After considering these suspects and more, everything comes to a head on October 5th. At the moment the killer knows he’s been discovered and is trying to flee town, Algerians surge into the streets to protest the shortages and high prices. The final chapters are full of reversals and unearthed secrets.

While many novels and scholarly works have been written about Algeria’s war for independence and its “black decade” of the 1990s civil war, little has been written about the mass protests of October 1988. “There were victims,” Khatibi says, “but no judgments.” He adds, “until today, there has never been a conference or a serious debate about October 5, 1988. Why? We are afraid to face our past.”

In The End of the Sahara, Khatibi brings us face to face with this past, reviving some of his city’s ghosts so that we can see them more clearly. The oldest of these ghosts are from Edith Maud Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik, which was adapted into a 1921 film starring Rudolph Valentino. Maud Hull’s novel is set in a hotel modelled after Bou Saada’s own, and a copy of The Sheik is passed around by characters in Khatibi’s novel. Maud Hull’s book begins with a dance held at a hotel, an echo of Zakia’s work as a singer in a hotel discotheque.

Today, these types of mixed dances have disappeared. “Men and women are separated. Foreigners come there less and less. In her novel, Edith Maud Hull wrote about a city that had [by 1988] already disappeared,” Khatibi says.

The novel marks the end of the famous—and real—Sahara Hotel, which not only hosted Maud Hull and many other tourists, but also a key meeting between the first president of Algeria and the man who deposed him, Houari Boumediene. Contemporary Bou Saada is very different from the city where this historic meeting took place, Khatibi says. “But people don’t want to hear about that past.”

Whether or not people want to hear about it, Khatibi is determined to explore his country’s past: as a journalist, as a translator, and as a novelist. Like several of the young characters in The End of the Sahara, Khatibi left Algeria to seek opportunity elsewhere; he currently lives in Slovenia. Yet he continues to engage Algeria’s ghost stories, listening to and imagining lesser-known voices so he can relay them to us, his readers.

Top photo: Chronicle / Alamy