Making Stone Speak

Sculptor Athar Jaber captures the beauty and the grotesque of contemporary society.

By Charles Shafaieh

Photographs by Benjamin Malick

Sculpting stone demands patience and discipline. For eight hours a day, Athar Jaber hammers a chisel against a marble block. Each cut alters the stone minutely. Jaber, an improviser who approaches his material without any set plans, must keep tapping for six hours or more before noticeable results emerge. And they come at the price of extreme physical strain. The next day, the cycle repeats, as it does day after day until the sculpture is ready for exhibition—a process that usually takes a year.

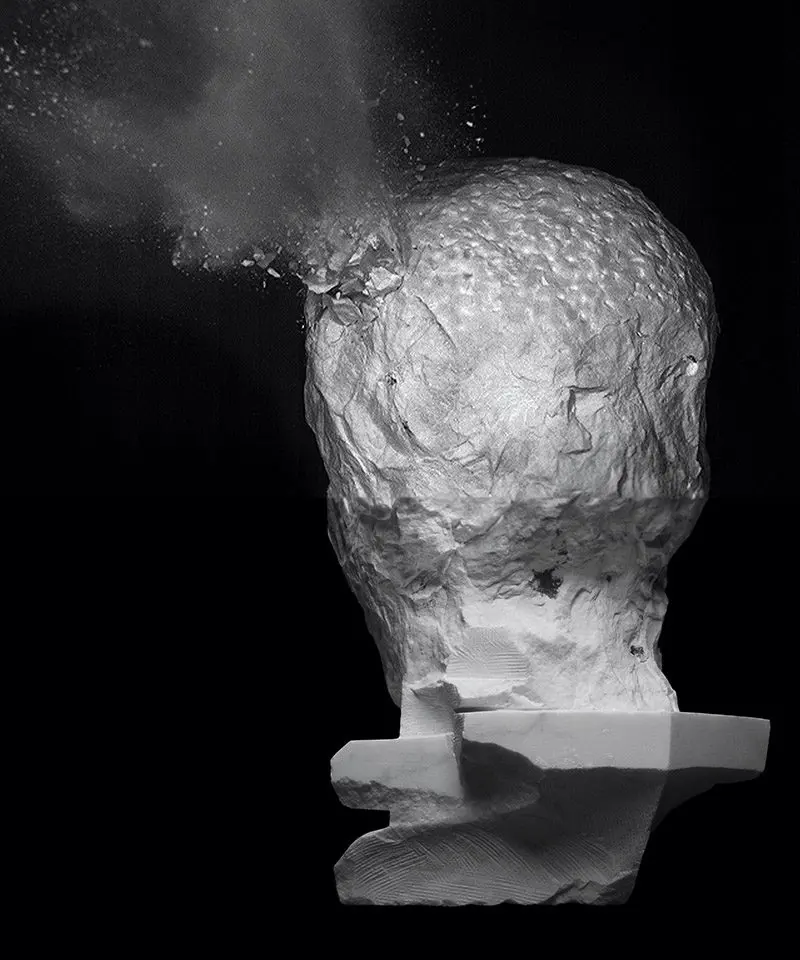

Jaber typically depicts body parts in states of unrest, fragmented and unnatural, metaphorically deformed and diseased. Eyeless faces seem to melt or twist violently; pristinely constructed ears burst forth from mouths; disembodied arms wrap around each other in displays of tension. He often juxtaposes polished features with still-rough stone. The bodies seem to push themselves out of the material and also undergo decay.

“Artists should reflect on the times in which they live,” Jaber says in his studio in Abu Dhabi, where he has lived since September 2023. “We are bombarded by images not of life’s beauty but of its horrors. I don’t want to offer an escape. Contemporary society is literally broken, fragmented, uncomfortable, so the integrity of the human body as intended in the Renaissance is not suited anymore.”

Sculpting stone demands patience and discipline. Jaber hammers a chisel against a marble block for eight hours a day. It can take a year for the piece he will exhibit to emerge.

The interplay between the beautiful and grotesque has been for him a lifelong constant. Born in Florence to Iraqi painters Afifa Aleiby and Jaber Alwan, he spent his childhood drawing Michelangelo’s David and The Slaves at the Galleria dell’Accademia. Back home, however, he watched footage from the first American invasion of Iraq, a country he had never visited. The continued violence in the region only deepened his aesthetic convictions.

An obsession with Florence’s sculptural bounty spurred Jaber’s total immersion in stone. As a student at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, he committed himself to the medium despite a curriculum that de-emphasised it in favour of figure modelling with clay and conceptual work. About four hours a week were allotted to stone sculpting, but he needed more time. “I spent days and nights in that studio,” he recalls. “I had to be there every day to absorb as much as possible.” No one else was as devoted, which he considers unsurprising. “It’s slow, heavy, dirty, messy, and not something that fits today’s time, when people want everything to be fast,” he says. When his professor retired, he offered Jaber the position immediately upon his graduation. Jaber stayed for 15 years.

His studio is, in many ways, home. “The hardest question you could ask me is, ‘Where are you from?’” he says. “Genetically, I might be Iraqi, but I was born and grew up in Italy. I have a Dutch passport, but I don’t feel part of that country. I lived in Belgium for much of my life, but I’m not attached to it. I feel I don’t have a country.”

The UAE attracted him because it is in what he calls its “golden age,” particularly regarding its investment in culture. Europe is in crisis, he believes, and he feels more energised here. After the year-long challenge of transporting his studio from Belgium, he is back at work in Musaffah, Abu Dhabi’s industrial area. The neighbourhood is fitting, he says. High ceilinged and airy, the studio features orderly shelves filled with busts that gaze down at large marble slabs waiting for Jaber’s attention. It is more than a workspace. “It’s the first dedicated stone-carving studio in the region, which gives it immense potential to become a hub for sculpture—a place where people can gather to learn about the craft through tours, events, and classes,” he says.

“Paintings exist on the wall, which isn’t our space, whereas a sculpture occupies space where you could otherwise move freely. It claims its presence.”

For Shot Head (2015) top, Jaber performed a variation of Michelangelo’s definition of sculpture—that which is done by means of removal—by firing 64 bullets at the marble. It was inspired by the destruction of ancient monuments such as Palmyra in Syria. Above, Jaber depicts body parts in states of unrest, fragmented and unnatural, metaphorically deformed and diseased. He juxtaposes polished features with still-rough stone. The interplay between the beautiful and grotesque has been a constant. Video still and above photo courtesy of the artist.

For this, he needs local support. Exhibiting helps. For the inaugural Public Art Abu Dhabi Biennial (on view until April 30), he participates with Clearing, a three-metre-tall block of marble with a haunting opening the shape of a human silhouette through which viewers can walk. He is also just closing his first solo show in the region, at Ayyam Gallery in Dubai.

Exposure centred on art helps toward building a community in his new country on terms that extend beyond national borders. “We live in a society divided by nationalism whereas the fabric of society is much more intricate and complex,” he says. Stone, by contrast, unifies people across time and space.

It doesn’t always attract spectators though. Compared to paintings, sculptures demand a heightened degree of attention, which, Jaber muses, may be why they are often neglected in museums. “They are aggressive,” he asserts. “Paintings exist on the wall, which isn’t our space, whereas a sculpture occupies space where you could otherwise move freely. It claims its presence.”

Were we able to touch them, which he advocates for his own work, they might appear less confrontational. “Sculptors always touch the work to check it is the shape we want,” he says. “Sculpture lives within the senses and needs to be experienced in that way as well.” By feeling the gaps where otherwise healthy body parts should be or the variations of rough and smooth textures suggesting scars of unknown origin, the relationship between viewer and object changes. It facilitates more nuanced interpretations of the bodies Jaber knowingly inserts into our space and, in turn, of our own.

For the inaugural Public Art Abu Dhabi Biennial, Jaber participates with Clearing, which features an anthropomorphic opening carved into a three-metre-tall block of marble. The passage invites contemplation. Photo: Lance Gerber.

Arguably we should be attracted to stone, as it has been vital to humanity for millennia. “We come from caves, where our first paintings were. Our first utensils and weapons were made of stone. Many iconic religious objects are stone including the Kaaba, the Western Wall, and the Anointing Stone,” he says. “From Assyria to Latin America, we’ve been carving it.”

Stone’s universality manifests in Jaber’s rejection of any cultural attributes or characteristics in his work. Whether through obscuring his heads’ physiognomies or, in the case of his votive series, casting body parts such as noses and eyes divorced from any corpus, they become timeless and universal. He instead directs the focus toward his methods. For Shot Head (2015), for example, he performed a variation of Michelangelo’s definition of sculpture—that which is done by means of removal—by firing 64 bullets at the marble, inspired in part by the destruction of ancient monuments such as Palmyra in Syria. The final texture of Woman’s Head resulted from an acid bath, evoking the alarming number of acid attacks against women worldwide. The work, he says, is also a commentary on acid rain, which corrodes public monuments, and other environmental issues. He leaves his works open-ended so that the associations they inspire will differ dramatically based on where and when they are exhibited.

Closure of any form dissatisfies him. “In my studio, I have pieces I carved over 10 years ago, and I question whether I should leave them as they are,” he says. Humans, he believes, are unfinished, always evolving, and his work should be no different. “When one finishes anything, it becomes one statement and is weaker. Even the universe doesn’t have clear boundaries! I like to keep things in constant development and growth.”