recipes for broken hearts

The inaugural Bukhara Biennial offers the tools to move beyond all that ails us.

What if a spoonful of rice could heal our aching hearts? This unconventional remedy—plov, Uzbekistan’s ubiquitous rice dish—was the solution that, according to legend, philosopher and physician Ibn Sina gave to a prince unable to marry the daughter of a craftsman.

This myth inspired the theme of the inaugural Bukhara Biennial: Recipes for Broken Hearts. Running until November 20, it unfolds across the restored caravanserais, madrasas, and public courtyards of this historical city.

Curated by Los Angeles-born Diana Campbell and Dubai-based Wael Al Awar, and commissioned by Gayane Umerova for the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, the event proposes a form of exhibition-making that responds to the spirit of the place: through collaboration with local artisans, the use of regional materials, and the activation of Bukhara’s architectural heritage.

The idea was to create a platform where Bukhara’s global influence could be interpreted by contemporary artists, revived and recognised anew. The peculiarity of this biennial is that all works are created in collaboration with Uzbek artisans, emphasising links between Bukhara and the rest of the world. “The entire programme is embedded in the surrounding context, materials, ingredients, traditions, the landscape, and even the local climate at [this] time of the year,” Umerova explains.

An example is a mosaic in the form of a stomach by Uzbek artist Oyjon Khayrullaeva, who worked with artisans Rakhmon Toirov and Rauf Taxirov: “My grandmother preserves recipes from the past—herbs, prayers, ancient rituals,” she says. “In her words dwell forgotten practices of healing, meant for both body and soul. Through her voice, I hear the Bukhara that once was, in whispers, in scents, in echoes that grow fainter with time.”

Addressing the theme, Campbell notes that “most forms of heartbreak are not romantic, and they often involve more than two people. This biennial is about reparation rather than heartbrokenness.” It is, she says, about the kind of wonder we knew as children that can spark the wildest sense of imagination.

Palestinian-Saudi artist Dana Awartani, collaborating with Nemat Ismatullayev, speaks of her work for the biennial as “a gesture of remembrance and a ritual of mourning”. It is, she says, a way to honour and uphold Palestinian cultural heritage that has endured and evolved through centuries.

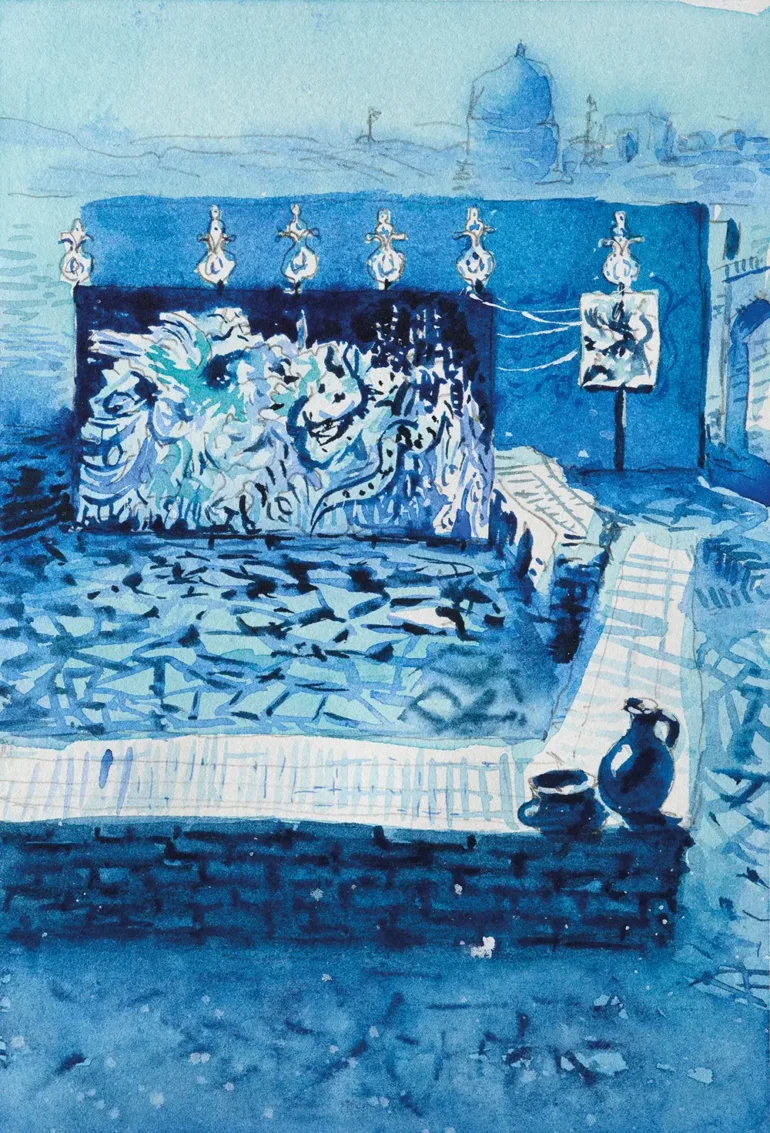

For Afghan-Australian artist Khadim Ali, who works with Sanjar Nazarov and Said Kamolov, myth becomes a container for grief. “After losing my mother, I began to see her in Simorgh, the mythical bird,” he says, “a healer of broken hearts, a presence that soothes the ache of longing, and a mother who returns in silence.”

The biennial brings together visual, culinary and performance art, as well as Uzbek, Central Asian and international artists, including Antony Gormley, Wael Shawky, Laila Gohar, and Subodh Gupta. All visions complement the curatorial concept of heartbreak as something too vast for any single remedy: “The biennial presents artworks that offer the instruments we need,” Campbell says, “ways to process, mourn, memorialise, and ultimately move beyond broken-heartedness.”—Naima Morelli

Image: Khadim Ali, in collaboration with Sanjar Nazarov and Said Kamolov.

Yunus Farmonov courtesy of Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation.