The Accidental Auteur

With “Goodbye Julia”, Sudanese filmmaker Mohamed Kordofani tackles racism in his homeland and winsplaudits at the Cannes Film Festival.

By William Mullally

Art exists for many reasons. For many creators, long before inspiration hits, they imagine a moment of validation, perhaps accepting an award. The art becomes a vehicle to get there. Those artists soak up the spotlight when it arrives, obscuring their work.

It becomes clear, moments into my conversation with Sudanese filmmaker Mohamed Kordofani, that he is not that type of artist. “Have you watched the film yet?” he asks. “If not let’s not do this, because my life is too boring to discuss.”

It isn’t. History was made on stage at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Kordofani’s debut feature, “Goodbye Julia”, received the Freedom Prize, becoming the first Sudanese film to win a prize at Cannes, and the first to be accepted to the festival at all.

“Goodbye Julia” centres on a woman named Mona from Khartoum, the capital, who is secretly responsible for the death of a man from the country’s south, and who employs his widow, Julia, to atone for her misdeeds. Mona soon learns that penance isn’t that simple and that good intentions alone cannot heal centuries of bigotry and racial division.

The film is dialectical in nature, a salon rather than a soap box. The characters are flawed and confused, with an unmistakable humanity and a capacity for both good and evil. Kordofani hopes that the people of Sudan can see themselves in the characters. They exist to spark a conversation on the streets of Sudan that he himself has been having for the past 12 years.

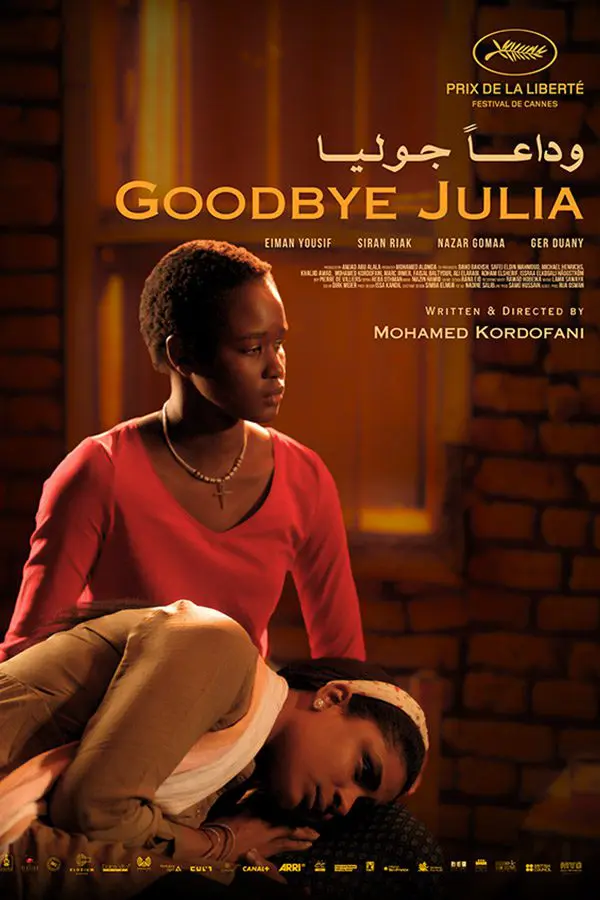

Eiman Yousif and Siran Riak played the lead roles, and the heart of the story, Mona and Julia. Photo: Mad Solutions.

He had never considered how much prejudice he had been conditioned to accept until February 7, 2011, when 99% of the predominantly black south voted to secede from the predominantly Arab north, forming the country of South Sudan. He asked why. The answer would change his life.

“I was brought up in a traditional Sudanese home, predicated on the values we’d inherited from the generations that came before us, both good and bad. I knew we were racist, but I’d been taught to accept that as a harmless fact of life, but it was clear that nothing could be further from the truth. I began to look deeply at every aspect of our society, accepting what I thought was good and rejecting what I thought was bad. It was a painful process, but it’s one that changed me completely,” he says.

“At the time of the secession, I was an aircraft engineer. That wasn’t my aspiration—I had wanted to study fine art, but my father wouldn’t let me. I never thought about being a filmmaker. I had always loved to write stories, but they were for me. Nobody ever read a word I wrote, and I’d mostly forgotten about that when my career got going. I moved to Bahrain, got married, and had a very practical, reliable career in front of me, just as my family had wished,” he says.

But, he began to ask, if so many of the lessons he’d been taught were wrong, why did he accept a path that was given to him?

“I was never a cinephile. I watched movies for fun, but I didn’t think about the people making them. That only occurred to me when I realised my head was full of stories, and there is no better way to reach normal people, to make them consider new ideas, than through cinema,” he says. “I took an online filmmaking course, and at the end we had to submit a scene. I flew to Sudan, began casting and scouting, and said to myself, ‘well, I might as well make a short film’. I finished it, and people came to watch—for the first time a story of mine had an audience. I started doing this every year on my annual leave, and the audiences grew bigger and bigger.”

The idea for “Goodbye Julia” came in 2018, during an argument with his wife, who wanted to get a live-in maid to help raise their newborn daughter. The moment triggered memories of Kordofani’s upbringing, a time when the domestic workers were black people from South Sudan. “It started clicking in my mind—the way we had treated them, and how this was linked to the separation of our two countries. I knew this would make a great story,” he says.

History was made on stage at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Kordofani’s debut feature, “Goodbye Julia”, received the Freedom Prize, becoming the first Sudanese film to win a prize at Cannes.

Kordofani (fourth right) in Cannes, with (from left) producers Amjad Abu Alala and Mohammed Alomda, and cinematographer Pierre de Villiers. Photo: Ammar Abd Rabbo.

“At the time of the secession, I was an aircraft engineer. That wasn’t my aspiration—I had wanted to study fine art, but my father wouldn’t let me. I never thought about being a filmmaker. I had always loved to write stories, but they were for me. Nobody ever read a word I wrote, and I’d mostly forgotten about that when my career got going. I moved to Bahrain, got married, and had a very practical, reliable career in front of me, just as my family had wished,” he says.

But, he began to ask, if so many of the lessons he’d been taught were wrong, why did he accept a path that was given to him?

“I was never a cinephile. I watched movies for fun, but I didn’t think about the people making them. That only occurred to me when I realised my head was full of stories, and there is no better way to reach normal people, to make them consider new ideas, than through cinema,” he says. “I took an online filmmaking course, and at the end we had to submit a scene. I flew to Sudan, began casting and scouting, and said to myself, ‘well, I might as well make a short film’. I finished it, and people came to watch—for the first time a story of mine had an audience. I started doing this every year on my annual leave, and the audiences grew bigger and bigger.”

The idea for “Goodbye Julia” came in 2018, during an argument with his wife, who wanted to get a live-in maid to help raise their newborn daughter. The moment triggered memories of Kordofani’s upbringing, a time when the domestic workers were black people from South Sudan. “It started clicking in my mind—the way we had treated them, and how this was linked to the separation of our two countries. I knew this would make a great story,” he says.

The idea was too big for a short film to be made on holiday. He started to develop it, telling filmmaker friends about the concept. Amjad Abu Alala, director of the groundbreaking film “You Will Die at 20”, wanted to produce it. But how could he pursue this calling in Sudan and continue the safe life he had built in Bahrain? It was 2020, and the pandemic stepped in.

“There’s no need for aircraft engineers when all flights have stopped. I was at home and I realised I didn’t want to go back. I was 37, and switching careers at that age is not easy to do, it may even be reckless. But what good is financial security if I’m miserable?” he asks.

He left it behind, even choosing not to renew his engineering licence so that he couldn’t change his mind. He dove headfirst into “Goodbye Julia”.

First, he would have to find his Mona and Julia. He couldn’t call a Sudanese casting agency—no film industry existed in the country. So he scoured the Internet. One day, scrolling through Facebook, he stumbled upon a livestream of a performance in Khartoum. The singer embodied the same strength and vulnerability that he imagined in Mona. But who was she?

“Luckily, the person filming kept panning from the stage to the crowd, and each time they did I looked at the faces. Finally, I spotted someone I knew and I texted, asking who it was they were watching. They told me her name was Eiman Yousif,” Kordofani says.

He found Julia soon after on Instagram. Her name was Siran Riak, a former Miss Sudan, now a model living in Dubai. He messaged her, but Riak questioned whether the offer was real. Kordofani convinced her—his producer’s film was on Netflix—then flew to Dubai to meet her.

On set, surrounded by collaborators he had met during his years making shorts, the challenge became getting the performances he wanted from his two non-actor stars. “Siran is a supermodel. She stands like a supermodel, she sits like a supermodel. So much of it is not just about how to deliver lines. I would tell her, ‘you have to kill yourself a little bit—kill that flamboyancy and glamour that is so innate to you.’ Once she understood, she really became Julia,” Kordofani says.

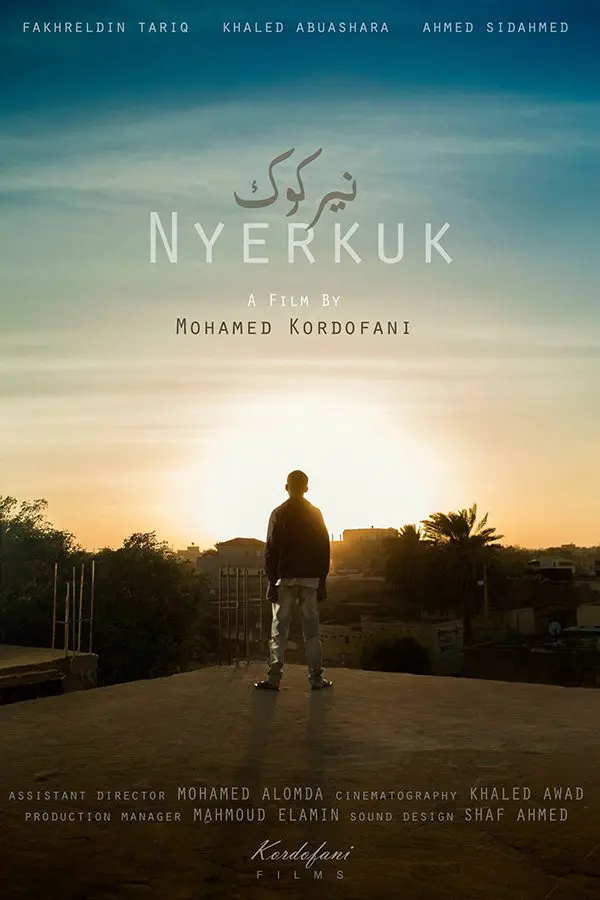

“Nyerkuk”, Kordofani’s second short film, won the NAAS Award for Best Arab Film at the Carthage Film Festival in 2016. “Goodbye Julia”, his debut feature, won the Freedom Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Posters courtesy of MAD Solutions.

He knew he could help her tap parts of herself that she’d never considered, because he had done it to become a filmmaker. When writing the film, he realised that each of the characters represented parts of himself at one time or another. Their journeys were his.

Kordofani lavishes credit on his team. “If I was alone, I probably would have pulled out a long time ago. But because these people believed in me, I had to stay the course, both for me and for them. There are so many people who worked tirelessly to help me achieve my dream, and their own. All of them inspired me, all of them put pressure on me in a way I really needed. Without them, I would have settled for a lot less than we achieved,” he says.

The big question remains how the Sudanese themselves will react to the film. It wasn’t until a screening in the summer at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic that a group of people who had travelled from Sudan finally watched the film. “When the Q&A began afterwards, someone asked how I thought the people of Sudan would view the film, so I diverted the question to them. One raised their hand, and said, ‘unfortunately, there is nothing we can deny in this film. All of these things happen. We just don’t talk about them.’ Now, I hope, we will,” Kordofani says.

His mother, who travelled with him to Cannes, and who marvelled at the celebrities on the red carpet, was confronted at the screening with many aspects of the life she herself had lived.

“She felt guilty at first. She said, ‘We didn’t mean to treat these people with any bad intentions.’ I said ‘Mom, I know, that’s how I could empathise with all the characters in the story’. She felt this was something good for the next generation. She’s even started having these conversations with others. She’s even confronting her own brother about racism. I had hope that I could reach the younger generation, but the fact that even people in their 60s are talking about these things is so heartwarming to me,” he says.

The conversations he was not prepared for are the ones about his own journey. As the film picks up steam, more people are coming upon his story, then reaching out to tell him how inspiring they find it, how it’s helping them make the choice to pursue their art when everyone tells them to be prudent. “I’m accepting it as I go,” Kordofani says. “I’m getting too many messages to ignore this.”