The Alchemy of Knowledge

After a career in diplomacy, including as Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the UK and the US, His Royal Highness Prince Turki AlFaisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud has devoted a significant share of his energy and intellect to cultural interests.

Interview by Catherine Mazy

Photograph by Katarina Premfors

In 1976, Prince Turki was one of the co-founders of the King Faisal Foundation, which in 1983 established the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies with the mission to transmit knowledge between Saudi Arabia and the world. Today, Prince Turki is its chairman. He speaks to Hadara in the context of KFCRIS’s Takwin: Sciences and Innovation exhibition, which exhibited its rare manuscripts and other artefacts at Sharjah’s House of Wisdom from December 2023 to March 2024. The exhibition honoured the remarkable contributions made by Muslim scholars during the Islamic Golden Age. From the start of the seventh century, these scholars played an important role in advancing the sciences. In the eighth century, they established a House of Wisdom in Baghdad and filled its libraries with an extensive collection of manuscripts.

Tell us about the exhibition and why Sharjah offered a fitting platform.

The importance of the exhibition lies in its highlighting science among Arabs and Muslims. It does so by presenting the relevant manuscripts, which are linked to the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah), one of the world’s largest public libraries that used to exist in Baghdad. Sharjah is one of the highly regarded platforms for such an exhibition that promotes Arab and Islamic culture.

What are the outstanding artefacts in the exhibition?

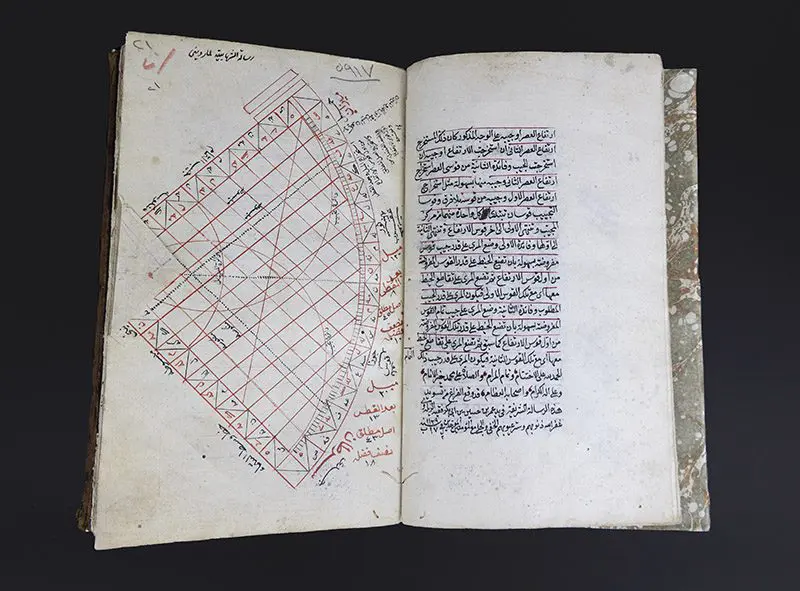

Every artefact presented is considered an important contribution to science. The exhibition highlights five scientific fields in particular—medicine, astronomy, engineering, mathematics, and zoology—and identifies the most prominent manuscript in each of these fields. For instance, in the field of medicine, the exhibition presents the manuscript of The Canon of Medicine by Ibn Sina, which is one of the most prominent medical books. For zoology, it presents The Life of Animals by Al-Damiri, which is one of the most comprehensive books in the field. It is edited in alphabetical order according to the names of animals, and describes the character, diet, life, and behaviour of each.

Another noteworthy book in the exhibition is The Politics of Horse written by Qanbar, which reflects his deep knowledge of the nature of horses, how to train them and deal with their behaviour, which he gained as a groom of Ali ibn Abi Talib’s horses. It epitomises how Arabs have cared about horses and equestrianism. In addition to exhibitions, the manuscripts and objects are always accessible for researchers through the “Services for Researchers” tab on the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies website.

The Takwin: Sciences and Innovation Exhibition brought its rare manuscripts and artefacts to Sharjah’s House of Wisdom from December to March. At the opening, HRH Prince Turki AlFaisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud was accompanied on a tour by HE Sheikha Bodour Al Qasimi, Chairperson of the Sharjah Investment and Development Authority, and HH Sheikh Sultan bin Mohammed bin Sultan Al Qasimi, Crown Prince and Deputy Ruler of Sharjah, and Chairman of the Sharjah Executive Council. Photo courtesy of House of Wisdom

How were the artefacts sourced?

The curators selected the pieces for the exhibition from the collections of manuscripts and museum objects owned by KFCRIS, which preserves more than 28,000 original manuscripts and 580 artefacts of Arab-Islamic arts. The exhibition did not require loans, and was completely worked on in-house, for its ideas, content, writing, design, and presentation.

Tell us about the name, Takwin, which is the ancient alchemy aimed at creating not gold but life, and not chemically but spiritually. Does the exhibition give life to Arab-Islamic scientific heritage?

Takwin carries a few meanings. It derives from the root verb “kawwan” which means “created”. It can also be used to mean “made”, “founded”, “erected”. In this case it means creation or how science is used to make things.

What is the main idea you want people to take away from the exhibition?

Through this exhibition, which presents a wide range of manuscripts and objects that highlight the role played by Muslim scholars in preserving human civilisation and scientific progress, we aim to introduce the immense legacy that used to fill the wings of libraries and the shelves of manuscript vaults. We hope to inspire current and future generations by opening before them wide horizons of scientific ideas, especially those in the fields where our pioneers excelled. The history of Islamic knowledge is full of pioneering achievements and innovations in various scientific fields.

Taghyir Al Risalah Al Mardiniyah fi Al Rub’ Al Mojayyab (Changing the Al Mardini Message on Sine Quadrant) by Abdulwahhab Qulah li Zadah. Written between 1577 and 1601 AD.

How do you view the work of KFCRIS?

When the founders of the King Faisal Foundation decided to establish the centre, they intended it to carry on the legacy of the late King Faisal, God rest his soul. A day before he died, he was asked by a reporter how he envisioned the Kingdom in 50 years’ time. His answer was that he envisioned the Kingdom as a wellspring of radiance for humanity. Under the leadership of the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, and HRH the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, that vision is coming true, alhamdulillah.

“The main challenge we face as peace advocates, promoters of heritage and admirers of great civilisations is how to protect and preserve cultural heritage,” you said in The Hague in 2019. Is enough being done to protect cultural property?

I am not fully familiar with all efforts to protect the world’s cultural heritage. However, I believe UNESCO is playing an important role in identifying what is needed to protect human heritage. Nation states need to value their own heritage and protect it. International and national civil societies should be guardians of preserving our human culture.

Can you make a connection between the glorious intellectual past that Takwin represents and the Arab-Islamic world’s present and future? What was it about the Golden Age that made it so outstanding?

In the Quran, God says, “O people, I have created you of man and woman so that you may know each other. The most exalted of you are the pious ones. God is knowing, he is aware.” How will we know each other if we don’t learn from each other? The Prophet Muhammad, God’s prayers and peace be upon Him, said: “Seek knowledge even in China”. That is why today, in both our countries, we are following God’s word and our Prophet’s hadith.

Stirrup Some consider stirrups to be one of the tools that contributed to the foundation of modern civilisation. Origin: Morocco, 18th century AD.

The King Faisal Foundation was founded with the mission to preserve and perpetuate HRH King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud’s legacy. Tell us about the work of the foundation today.

The foundation has established schools for boys and girls from kindergarten to baccalaureate and the AlFaisal University for men and women. It also gives the King Faisal Awards in five disciplines: Service to Islam, Islamic Studies, Arabic Studies, Science, and Medicine. Plus, the work of the centre. It has also done social work to benefit the poor and a scholarship programme for bright students to study not only in its schools and university but also abroad in foreign academic institutions.

The Middle East, you said, “is a region of diversity and inclusivity that can compete with any in the world and can serve as an engine of economic growth and human ingenuity.” What will it take to unlock this vision of the future?

Free ourselves from the traps of ideology and conflict by bringing the region to a common futuristic vision where we cooperate to bring peace and stability to our region free of foreign interference.

US President John F. Kennedy once said that political leaders must learn from the mistakes and failures of the past. The Israel-Palestine conflict has plagued the Middle East for decades, yet nothing has changed. It is time, you said in a speech to the National Council on US-Arab Relations in November, to address the plight of the Palestinian people once and for all. How can we break the patterns that have delivered so little? Does the desire for peace still exist?

It seems that George Bernard Shaw’s axiom is more accurate regarding history: “We learn from history that we learn nothing from history.” The failure to learn from the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict and the failure of all concerned to address its root causes is behind the continuation of this conflict. I am sure that the Arab and the Palestinian desire for peace still exists. However, all attempts to achieve a just peace were dashed by the refusal of Israel and its sponsors in the West to abide by related UN Security Council resolutions and by not accepting other initiatives to end this protracted conflict. The alternative to peace is more wars and instability in the Middle East.

The Global Stocktake agreement, adopted at COP28 on December 13, is the first COP text that has called on countries to wean themselves from fossil fuels. Does the commitment to “transition away” offer a more realistic approach to the challenge of replacing oil and gas?

I think we need to wait to see if the parties keep to their commitments. However, I do not see any real alternative to oil and gas in the near and far future.

Saudi Arabia is undergoing a remarkable transformation as Vision 2030 imagines life beyond oil. At this midpoint in the Vision’s implementation, how do you assess progress, and what do you foresee at its completion?

Our Vision 2030 is a work in progress, and all indications lead me to conclude that we are on the right path to the future. The will and enthusiasm to succeed is as solid as when it began.

A small jar (Bernaih) A clay vessel used in the field of pharmacology to store medicines and herbs. Origin: Persia. Above, Sine Quadrant A handheld astronomical instrument in copper. Origin: Iraq or Persia, 18-19th century AD.

All manuscripts and artefacts courtesy of King Faisal center for research and islamic studies.