Finding magic in the mundane

Abu Dhabi-born artist Farah Al Qasimi’s photographs and videos are imbued with a warmth and respect for her subjects that highlight the wonder in the commonplace, garnering attention from New York to London to Dubai.

By Charles Shafaieh

Photograph by Emily Hlavac Green

Artist Farah Al Qasimi’s affinity for the almost-otherworldly started young. She recalls childhood visits to Marina Mall Abu Dhabi, with glee, even reverence. “It was so bad! There were pools of stagnant water everywhere,” Al Qasimi says. “The scariest part was the tunnel, where you walk over a bridge with a constantly rotating starry sky. What it does to your sense of balance is spectacular. It was just this scrappy little thing that took 30 seconds to go through, but it has always stuck with me. I would go back again and again, to this alternate dimension where possibilities were boundless.”

Al Qasimi revels in showcasing the marvelousness of the banal, and how even what we know is fake can conjure happiness. In her photographs and videos, which are in numerous major collections including the Tate Modern and the Guggenheim, the acid colours of perfume bottles, mouthwash, and plastic furniture reveal their strangeness, as Al Qasimi compels us to examine them anew in her novel framing. A fan of the exaggerated worlds of anime, she demonstrates through images of hooded falcons, rows of niqab-clad mannequin heads, or a chandelier sparkling over Pringles cans in a New York bodega that the fantastical is not foreign to the everyday.

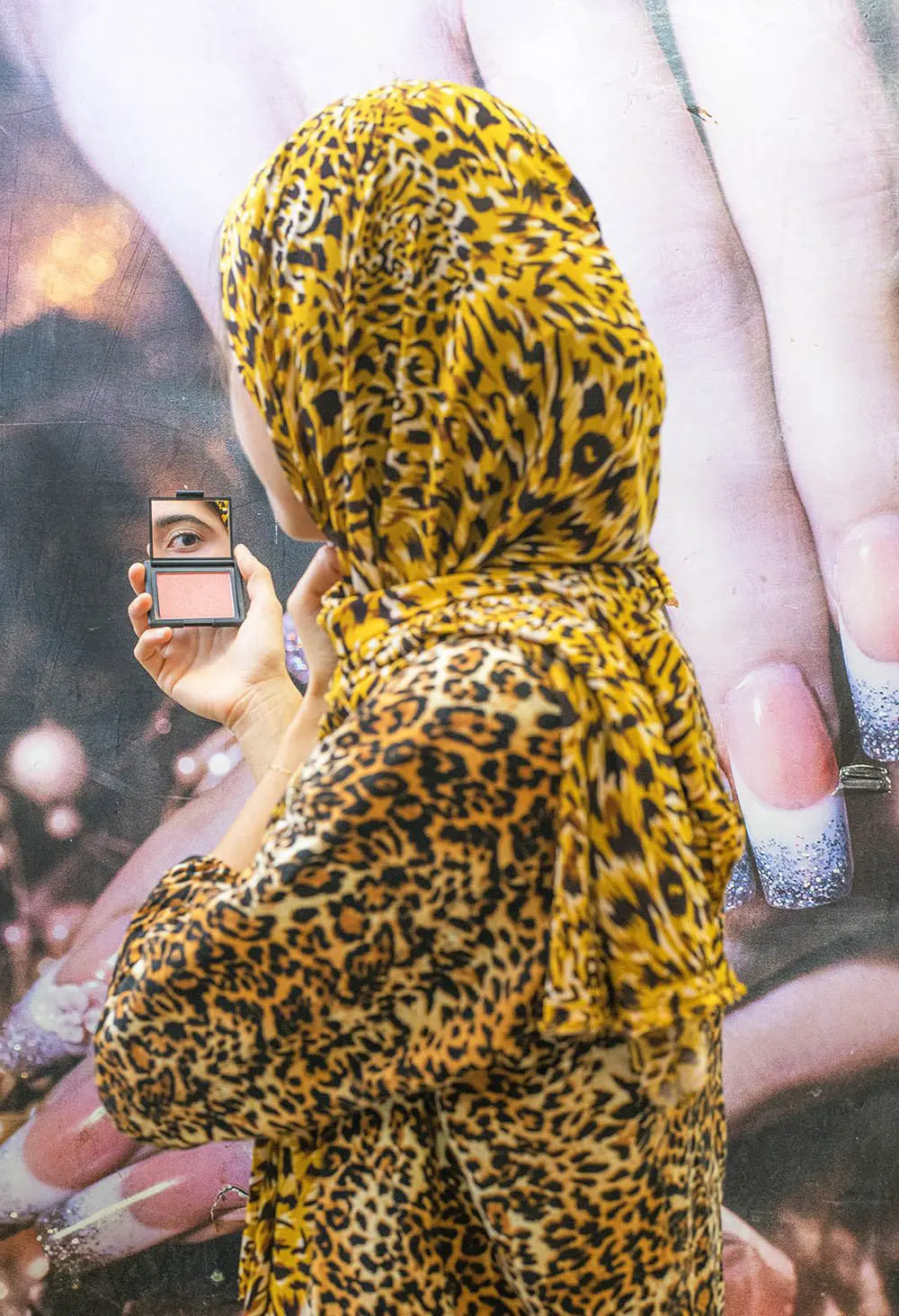

Woman in Leopard Print (2019) from Back and Forth Disco, a series of 17 photographs taken across New York City.

Born in Abu Dhabi to an Emirati father and a Lebanese-American mother, Al Qasimi attended Yale University, where she studied music before switching to art and continuing for a master’s. It was there that she became fascinated with this false dichotomy, thanks to an interior-decorating “failure.” “I bought a wallpaper mural of a beautiful beach, probably somewhere in Thailand, because I had seasonal depression. It was just a stock-footage beach,” she says. “I tried to hang it on my wall and didn’t do it well. The way it hung from my uneven wall and caught the light turned it into something else, beyond one flat image.”

Surfaces, whether the video screens or the mirrors which heavily populate her work, constantly trick us. All photographs, not just the dreamlike, are deliberately framed to exclude material and to play with our attention and emotions. Al Qasimi credits her growing understanding of photography to a stock image of a beach. In doing so, she imbues that wallpaper with a transformative power—just not one its manufacturers intended.

This anecdote may lead some to read her technicolour aesthetic as kitsch. However, that characterisation strikes Al Qasimi as an accusation. “There is often a classist connotation to the vocabulary around ‘kitsch’ that is not part of, or connected to, the visual language with which I grew up,” she says. “I was surprised when I first started hearing my work described as wacky and gaudy, because I don’t see it that way. When I go into a bodega owned by somebody from Yemen, I feel an immediate sense of recognition for the decor used—a fake sky, a certain kind of tile. That’s more interesting to me than ideas of high and low culture.”

Top, Farah Al Qasimi: Everywhere There is Splendor, installation view, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, September 3, 2021 to February 27, 2022. Above, Bodega Chandelier from Back and Forth Disco. The series celebrates individuality and the aesthetic choices that make spaces and surroundings uniquely personal.

The objects with which people choose to populate their personal spaces, whatever they might be, fascinate her. “It’s really interesting to me, on TikTok, to see how people decorate their bedrooms. Do they have pink lighting? Do they have a thousand Beanie Babies on their bed? I relate to the problem of creating a mirage for yourself, where you can astral project and just feel something different,” she says, in her compact home studio in Brooklyn, New York, where she has lived since 2017 and has decorated with plastic children’s toys, a keyboard she uses to compose the scores for her videos, and a collage of images on the walls ranging from huge paradisiacal landscapes to smaller photos of Arab food.

Her interest in the quotidian stems in part from cartoons, especially those she grew up watching on annual visits to her mother’s Lebanese relatives in America. “It’s hard for me not to look at objects in my house and think they have a little life of their own when I leave. It’s very Disney, with the mop coming to life and dancing down the hall.” Horror films also inspire this attraction. “Poltergeist is one of my favourite movies. One of the first explanations of poltergeists was people’s misplaced energy, which they somehow psychically transferred to objects around the house. I probably sound a little New Age-y, but I think the things we live with have a real reciprocity in terms of what they’re doing with us.” That conviction manifests in her apartment which, unlike her studio, is restrained in its mostly white decor. “I choose to have a room that’s an explosion of colour. I want to enter that world but don’t want to be in it all the time.”

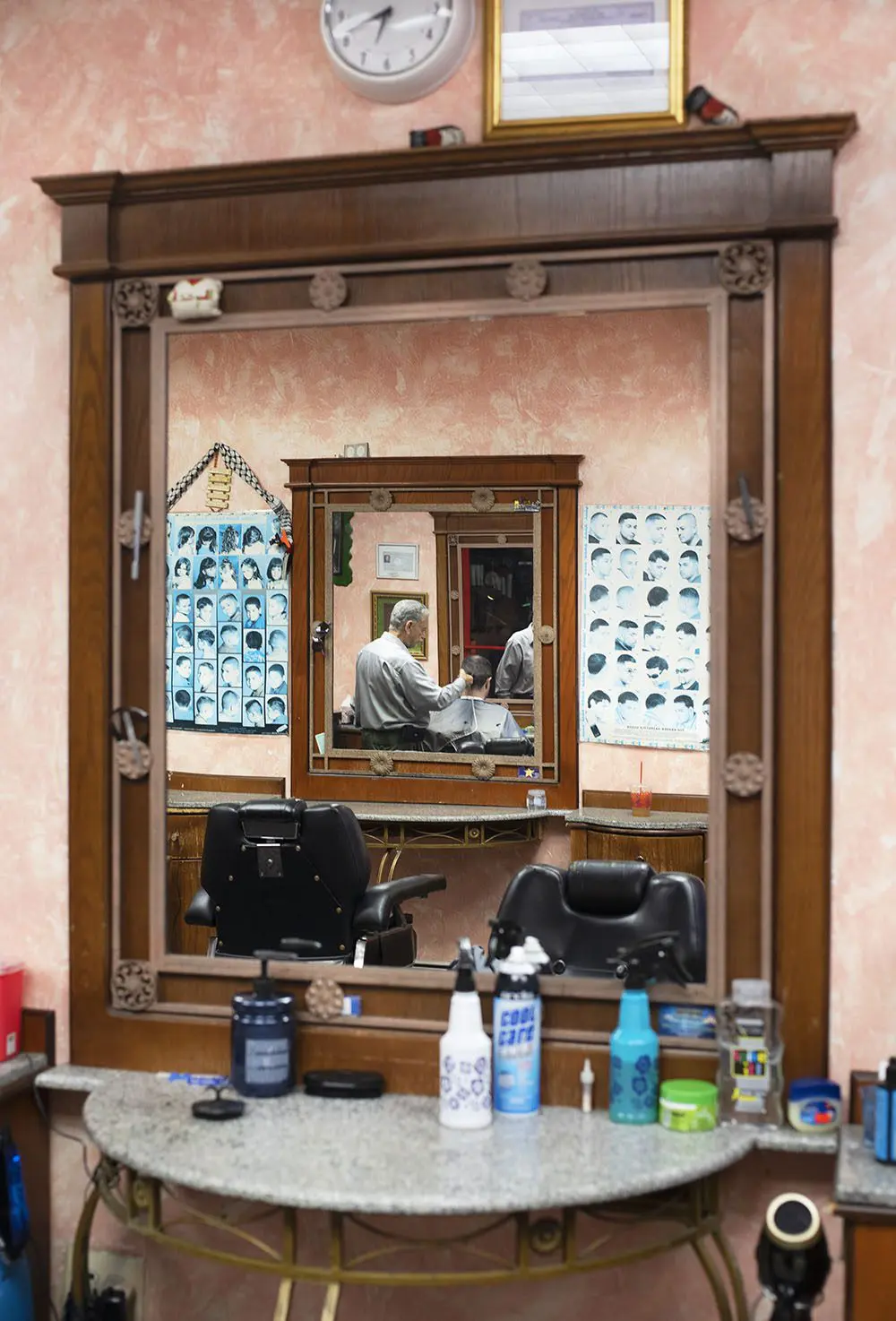

5 Star Barber Shop from Back and Forth Disco. The series isolates and highlights the beauty of seemingly inconspicuous moments amid New York City’s visual and audible noise.

Her attention to the objects that people purchase is not an explicit commentary on capitalism. At the same time, she is fully conscious of advertising’s techniques. “There are conventions to picture-making that I’m interested in utilising to lead you to what I want to show you,” she says, gesturing to a building-wide Cartier ad outside her window as an example. “That ad is really focused on the glistening metal of the jewellery; a makeup ad shows you the glossiness of the lips. I’m aware of the capitalist tendency to hyper-inflate textures and surfaces into much more extreme versions than they really are. But I’m not trying to do that with something that isn’t already there.” Despite her interest in escapism and fantasy, she is consistent in her affinity for reality. For her, photography and video serve as a means to bear witness that is distinct from creating entirely from the imagination, as a painter might do in their studio.

Back and Forth Disco (2020), a series of 17 photographs taken across New York City, highlights her preoccupation with her surroundings. Commissioned by New York’s Public Art Fund and displayed at bus stops, it was one of the few exhibitions viewable at the beginning of the pandemic. In one image, a woman in a leopard-print hijab and blouse, her back to the camera, looks at herself in a pocket makeup mirror, her eye the only visible part of her face. In another, a barber cutting hair is seen through a series of mirror-within-mirror reflections; flanking his station are posters, featuring various hairstyles, that have taken on an inexplicable cerulean tint.

“I focused on small, immigrant-run businesses because they are what keep New York City running,” she says. “I don’t know what I would do without some of them—without the Palestinians who run the bodega around the corner who ask me in Arabic how my day is going. This moment of familiarity is really important when you’re in a city that’s so big and that can be cold and impersonal. I wanted to use those very expensive advertising spaces to highlight some of these places.”

While some New Yorkers experienced rec- ognition, others were bewildered, as Al Qasimi didn’t utilise the bus-stop displays in ways people had been habituated to read them. “Someone took a photograph of Bleached Advertisement—a photograph I took of an advertisement that features a woman’s face, her features almost entirely bleached out by exposure to sunlight—and posted it on Reddit. They wrote, ‘Could someone tell me what this is an ad for? It’s really creepy.’ I like that somebody was so unsettled that they had to go to the internet and ask, ‘What the hell is this?’”

Noora’s Room (2020) was shown in the Lady Lady presentation at Cooper Cole in Toronto in 2021. In this body of work, Al Qasimi explores themes of mimicry, commodification, and escape as they relate to photography and global aesthetics.

Bewilderment is not an uncommon response to her pieces. Yet the confusion does not often stem from the too-muchness and colour saturation of her kaleidoscopic images, but rather from the viewer’s inattentiveness to the world around them. “I happened upon a tour of schoolboys at my last show in the Emirates and heard one of them say, ‘Why soap?!’ It was such a funny thing. They were really into parts of the show but then said, ‘We see that every day!’” Her excitement is audible as she recalls this moment which, in a way, validates her practice. “You see it every day, but how often do you think about what it really is?”

Like the perfume and food which are also her frequent subjects, soap has an intimate relationship with the body. Although she often hides people’s faces, stemming in part from the value Emirati women place on privacy, photographing these objects is still revealing. “Objects are often my answer to how you photograph things that cannot be seen,” she says. “When I photograph soap, I’m trying to photograph something that touches a body. When I photograph food, I’m trying to photograph care. For me, care looks like watermelon that is perfectly sliced or a rose made of tomato skin.”

Arrival, Al Qasimi’s third solo exhibition, at The Third Line gallery, Dubai in September to November 2019, used the language of horror cinema to reveal a new body of work featuring jinn folklore from across the UAE.

Unexpected and idiosyncratic links are a conscious hallmark of Al Qasimi’s, including in her new film, Mother of Fog, made for this year’s Sharjah Biennial. Examining harsh value judgments such as good and evil that she considers naive and self-satisfying, she looks at allegations of piracy against the Al Qasimi tribe made by the British East India Company, which furthered British colonial rule and economic gain. Embedding her research in an imaginative form, she fuses 18th and 19th century history with contemporary popular culture, in one instance via an interview with a former cargo- ship captain in the Gulf who now impersonates The Pirates of the Caribbean’s Jack Sparrow on a dhow he sails on the Dubai Creek.

Al Qasimi believes the impulse to make such disparate connections derives from her being of the generation who grew up alongside the internet. An older millennial artist (a categorisation she readily accepts, unlike being pigeonholed along nationalist lines), she is cognisant how not having that technology and then suddenly being able to explore global culture with a mere click was “like a portal opening.” “That everythingness to which I’m attracted comes from having a sustained awe at what happens when you have that access.”

Akin to her lasting fondness for that shoddily constructed funhouse from her youth, everyone, she suggests, should be attentive to the surprises and wonders in our daily lives. “I’m really conscious of how important it is to have that kind of joy—where, even if you can see the seams, you’re willing to be tricked because you’re committed to being surprised,” she says. “It’s the same reason we watch scary movies: We know they’re fake, but we’re still fully entrenched in the experience. That’s what art can do.”

Portrait of Farah Al Qasimi: styling by Oluwabukola Akinyode, Makeup by Sena Murahashi. Stylist Assistant Rashied Black. Top & Skirt: Rentrayage. Socks: Stylist’s Own. Shoes: Vintage Miu Miu. Jewellery: Wolf Circus. All other photos courtesy of the artist and The Third Line, Dubai.