The Doctor will see you now

Through his clothing brand Emergency Room, fashion designer Eric Mathieu Ritter aims to provide a sustainable and ethical alternative to fast fashion.

By India Stoughton

Photograph by Abed Khalife

When Lebanese-French designer Eric Mathieu Ritter founded his own label in 2018, he called it Emergency Room because, he says, “fashion is sick.” His ethical, sustainable brand serves as a small-scale, localised medicine, resuscitating unwanted clothing, one garment at a time. “It’s really about trying to do things differently,” he says, “to be an emergency room for social and environmental problems.”

Fast fashion is one of the world’s most polluting industries. Each year, 100 billion garments are produced—more than one new item every month for every person on earth. The industry produces 20% of global wastewater and up to 10% of global carbon dioxide output—more than international flights and shipping combined—with emissions projected to double by 2030.

And it isn’t only production and distribution that are problematic. Globally, just 12% of the material used for clothing is recycled. Many garments donated to charities in wealthy countries are sent to the markets—and eventually the landfills—of such countries as Ghana (where they are known as “dead white man’s clothes”), Haiti, Kenya, Sudan and Lebanon.

Ritter can’t stop fashion giants from producing billions of garments each year, but he can find ways to keep them out of landfills. Extending the usage of garments by nine months would reduce carbon, water and waste footprints by an estimated 20% to 30% each year, according to climate-action NGO WRAP. Emergency Room seeks to do just that, transforming deadstock fabric and vintage materials that are locally sourced to create unique garments in an ethically conscious ready-to-wear line. It also provides stable, fairly paid work for two shirtmakers and a collective of seamstresses in Tripoli.

Ritter always wanted to work in fashion. After his first industry placement at age 14, he spent his summer holidays interning in everything from sketching to sales to sewing. After graduating from the Lebanese branch of ESMOD, a prestigious French fashion school, he worked with designers in Paris and Beirut. However, he felt unfulfilled. “I was working on eveningwear pieces that neither me nor my friends were able to afford or even wear,” he says. “At that point I think I was demotivated and wondering if I had made the right decision.”

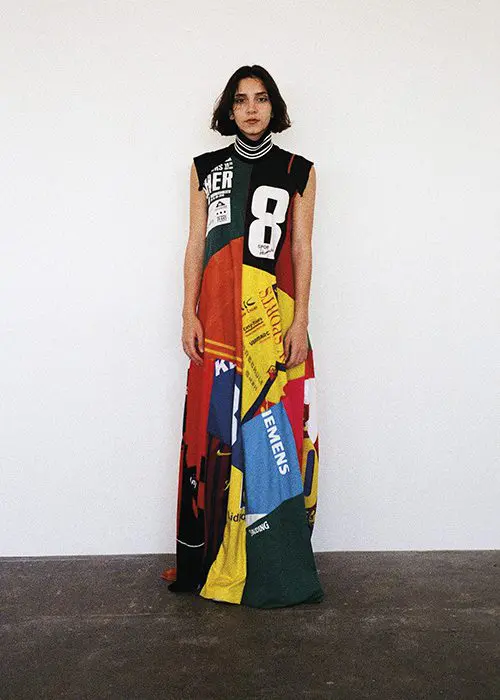

Clockwise: The 2022 collection Borderline explored the concept of nation states, borders, passports and flags. Second, the Neverland collection at Arab Fashion Week, October 2021. Third, the brand showcases clothes on people of all genders, ethnicities, body types and ages. The model wears the Borderline collection. Fourth, the designer’s grandmother, Hoda, has modelled for the brand’s campaigns. Photos: Emergency room (3); Hoda by dunia chahine

It was a job with Tara W Kheit, a charity that teaches sewing, embroidery, knitting and crochet to women in Tripoli, that helped him realise he had chosen the right career—he had just been doing the wrong jobs.

“This experience of getting out of my comfort zone made me realise that there’s a whole world out there that is beyond what I know,” he says. “I connected with lots of very skilled seamstresses and tailors that were all complaining about not having enough work, while at the same time discovering the souks of Tripoli, which are filled with second-hand clothes and materials that generally come from Europe and that stem from the problem of overconsumption that we all have. And that’s when it clicked.”

Today, Ritter scours Tripoli’s souks for garments and textiles that can be deconstructed and redesigned to create stylish yet practical clothing. Old jeans and denim jackets are cut up to make a line of casual patchwork garments. Printed bedsheets are transformed into smart shirts and shorts. Even outdated ties find new lives as colourful crop tops.

Ritter sells his garments online and in his two Beirut stores. Prices at Emergency Room start at around $60 and run to $420 for the most complex designs, allowing him to pay the garment workers fair wages. His more-affordable sub-label, Overworked, created in response to Lebanon’s ongoing financial crisis, carries dyed, over-printed and embellished garments, most priced between $10 and $60, aimed at teens and young adults.

Emergency Room doesn’t focus only on promoting awareness about ethical and sustainable fashion. The brand also challenges harmful fashion industry norms. Instead of hiring professional models who adhere to narrow industry standards of beauty, Ritter works with friends and acquaintances and even scouts people on Instagram, showcasing his clothes on people of all genders, ethnicities, body types and ages—including his octogenarian grandmother.

“By nature, because we produce pieces with upcycled materials, we have a lot of unique pieces, and we wanted to focus on that and promote the idea that we’re all different as human beings and that we shouldn’t actually want to look like each other,” he says.

He celebrates individuality in his runway shows, too, at times flummoxing organisers. All the garments Ritter designs for Emergency Room are intended to be gender neutral.

“It’s quite challenging because we show during menswear and during womenswear and every time we try to get a mix of men and women and people who don’t look like either and to challenge, bit by bit, the perception of things and the binary,” he says. “I think people as individuals are more on board with this concept than the industry itself.”

His collections often address complex ideas. In 2021, Neverland explored the need for a new perspective on Lebanon. “It was about coming to terms with the fact that our generation was sold a dream by our parents, who, as we grew up, kept telling us about Lebanon being the Switzerland of the Middle East, land of culture,” he says. “The reality is that this country is not what we idealise it to be.”

At a runway show in Dubai for Arab Fashion Week that November, instead of pounding music, he played a pre-recorded monologue reflecting on this idea, much to the surprise of his audience. The goal was to show people “that by staying, we could eventually make Lebanon a better place, but we first have to accept it for what it is, instead of imagining a version of it that is not true.”

In his 2022 collection, Borderline, he expanded on this idea to explore the concept of nation states, borders, passports and flags, and the theme of “travel restrictions, freedom of movement, and the fact that we’re not all free to move equally.” A series of simple white shirts and shorts, embroidered with visa and entry stamps, contrasted with longline burgundy blazers, emblazoned on the back with an invented passport cover featuring the words “Kingdom of Neverland” in Arabic and English.

The collection also included colourful patchwork garments made from recycled sports jerseys and flags. It highlighted the environmental impact of producing millions of polyester products destined to end up in landfills. But it also had a more symbolic meaning: “the idea of taking anything that divides people into groups and pits them against one another and cutting them up to join them together in one piece.”