The man in the mirror

Turkish artist Refik Anadol creates hypnotic digital installations in collaboration with artificial intelligence, which he sees not as humanity’s rival but its reflection.

by India Stoughton

As a child, Refik Anadol was enthralled by alien technology, artificial intelligence and futuristic worlds. It is fitting, therefore, that the work he does today would once have been thought to be the stuff of science fiction.

Born in 1985 in Istanbul, the pioneering Turkish-American new media artist steeped himself in sci-fi as a child. A formative encounter with Blade Runner—Ridley Scott’s 1982 adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s seminal novel about artificial intelligence, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, in which machines are programmed with human memories—kindled a fascination with the idea of a machine mind. That same year, Anadol got his first computer, and a lifelong interest in the relationship between human and machine was born.

“Watching a science fiction movie as a child is very different, because we don’t want to see the dystopia,” he muses. “As a child, we see the hope. We see a positive world around us. I think I felt so connected with even the darkest concepts of science fiction. You can still feel beauty. You can still find the human in there.” He describes the elusive element of sci-fi that so strongly captured his imagination as “this feeling of remembering the future.” Now living in that future, Anadol has cemented his place in the top echelons of the international art world with his innovative digital sculptures that stand on the cutting edge of AI technology.

As the first artist-in-residence at Google, in 2016, he learned how to harness machine learning in an artistic context. Today, he describes his work as an equal collaboration between human and machine. His large-scale immersive installations feature hypnotic visual sequences generated by artificial intelligence from huge data sets. Although each work is rooted in unique source data, they all stem from Anadol’s desire to answer a question that has consumed him since childhood: if a machine can learn, can it dream?

Refik Anadol photographed by Efsun Erkilic.

“For me, data is not numbers. Data is a form of memory, and this memory can take any shape and form. Every single AI endeavour, every single breakthrough starts with data.”

Honed over years of experimentation at the forefront of AI development, Anadol’s otherworldly works showcase what he calls machine hallucinations. Much of his work possesses a recognisable aesthetic—a mesmerising pattern of movement in which tiny spheres of colour multiply like bubbles, exploding outwards to create ever-shifting currents and half-glimpsed forms. But each piece is shaped by a unique dataset that determines its direction and parameters. The data he uses has spanned diverse subject matter including photographs and documents shared by the inhabitants of Seoul, MRI scans of the human brain, extracts from Turkish media, real-time wind, temperature and humidity reports from the Amazon, airport statistics, NASA archival photographs, and an archive spanning 200 years of art history, courtesy of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where he attracted vast crowds with his 2022-23 work Unsupervised.

“For me, data is not numbers. Data is a form of memory, and this memory can take any shape and form,” Anadol says. “Every single AI endeavour, every single breakthrough starts with data.” He describes the datasets that form the foundations of each artwork as his pigments and the AI as his brush. “I don’t think we should be stuck in Newtonian physics: a drying pigment, gravity… I think we can liberate the pigments. We can liberate those molecules and let them freely enjoy any dimension,” he says. “I feel like every single archive can have a similar aesthetic, but the core values of the movements, the colour, the speed, the behaviour, the gesture—they’re all new vocabularies.”

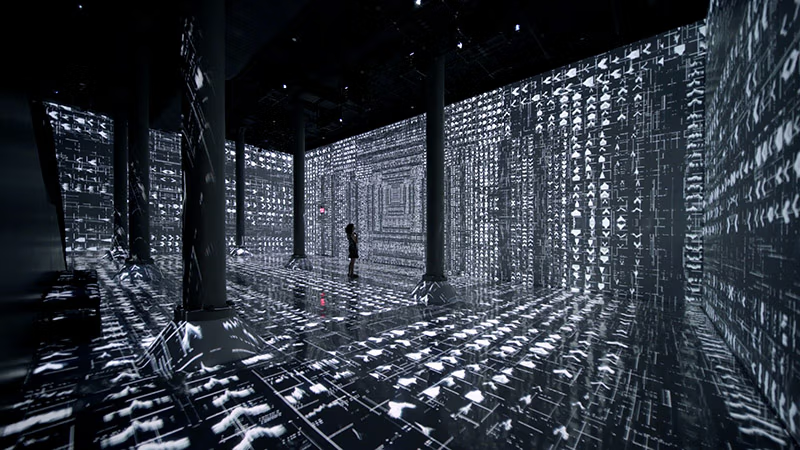

Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, top, Serpentine North, London, 2024. The exhibition enveloped viewers in immersive environments that utilised years-long experimentation with visual data of coral reefs and rainforests. Photo by Hugo Glendinning. Machine Hallucination – NYC, above, a time and space exploration into New York City’s past and potential future.

Courtesy of Refik Anadol Studio.

His use of AI allows him to work on a scale too vast for the human mind. To date, his projects have incorporated more than 4.5 billion images. But creating the work is not simply a matter of plugging in the data and allowing an AI to interpret it. The results Anadol strives for requires human input at “every single moment. We have a team of 16 people who can speak 15 languages and come from 10 countries,” he says. “The core team is really hands-on. Every parameter, every decision is extremely important for art making, and there’s lots of failures. What we see is a process of many, many failures.”

As part of his determination to push the boundaries of what’s possible on both the artistic and technological fronts, Anadol insists on selecting his own data and training his own AI models. “It’s a vision. It’s a purpose. It is truly the core fundamental layer of art making,” he says. “I do not see a breakthrough on an existing AI model… Once we break things, when we reconstruct things, find a new purpose and meaning, that’s where I believe that art happens.”

By working in a collaborative manner with AI, he says, he is searching for the human in something non-human. “I think that’s how we can understand AI before it becomes profoundly everywhere,” he says. “That’s a place where we demystify AI, we talk about it… I believe the more we understand something the less we have fears.” The more the public understands about how the technology works, the more likely it is that “we can use it for something beyond us, maybe something good for humanity,” he adds. “I believe the only way to make AI right for humanity is to bring everyone’s voices together.”

“Everyone” extends to the indigenous tribes of the Brazilian Amazon, where Anadol lived for several months with the Yawanawá community while working on Artificial Realities: Rainforest. It was one of the works on show at London’s Serpentine Gallery in the spring in the exhibition Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive, which investigated the ways in which technology alters our perception of the natural world. Also shown there was Artificial Realities: Coral, a sound and video experience highlighting the vital role of coral reefs in the ocean ecosystem, and Living Archive: Large Nature Model, which wrapped the gallery walls in an AI’s vision of a rainforest, generated from data of flora, fauna and fungi collected in 16 locations worldwide. The exhibition attracted almost 70,000 people.

Machine Hallucinations – Coral Dreams An AI data sculpture designed for Art Basel Miami 2021 and displayed on Miami Beach. Anadol and his team collected 35,742,772 images of coral and processed them with machine learning classification models. Photograph by Steve Kehayias, Courtesy of Refik Anadol Studio.

It combined Anadol’s signature flowing abstractions with a new aesthetic—hyperreal images of eerily plausible computed-generated flora and fauna. Fantastical birds and butterflies, vivid blooms, verdant forests and seemingly endless permutations of brilliant coral imagined by a machine adroitly mimicked those produced by billions of years of natural selection. Paradoxically, the believability of the permutations dreamt up by the AI served only to highlight the unparalleled creativity of nature.

The installations showcased the abilities of Anadol’s Large Nature Model—the world’s first open-source generative AI model dedicated to nature. As technology has advanced, Anadol posits, humanity has become increasingly disconnected from the natural world. “I think we forgot how incredible nature is,” he says. “We forgot that nature is the most intelligent thing we have.” Counterintuitively, he hopes that AI can change that.

“Large Nature Model is our big dream,” he says. Trained on data from organisations including the Smithsonian Institute, London’s Natural History Museum, National Geographic, CornellLab, and the Conservation Research Foundation Museum, as well as the archives of several botanical gardens and millions of images collected by Anadol’s team, the model assimilates billions of images and uses them to create detailed imaginary lifeforms. Anadol sees the model as “a teacher of nature,” as well as a means of encouraging ecological efforts and highlighting the dangers of climate change.

The model will form an integral part of Dataland, a museum dedicated to AI that Anadol plans to launch next year both online and in a physical location. Within a decade, he predicts, “AI will be in every step of life.” Ever the pioneer, he has begun taking steps to make his own work more sensory and immersive, from works that respond to changes in light, movement and acoustics, to incorporating sound and even custom-blended scents.

“We are going beyond just the image,” he says. “Like, what happens if computers sense us? What happens if our brain, our body becomes a part of it? What happens if our sensory inputs become this new output? And what happens if we go beyond image, sound and text? We are speculating that there is a world beyond this basic understanding of AI. There is a world where we can step inside machine dreams… It just needs to be invented.”

Ultimately, just as his Large Nature Model serves to highlight the sublime creativity of nature, he believes AI has the capacity to facilitate profound reflection on what it means to be human. “AI is a mirror for humanity,” he says. “It’s all about us, not about AI. If we just remind ourselves what it is there for, I think we’ll have a much greater understanding.”