TRADITION AND TECHNOLOGY

At Studio Ibbini, a collaboration between human and machine creates works that intersect contemporary art and engineering.

BY NICOLA CHILTON

It’s a hot June day when Jordanian-British visual artist and designer Julia Ibbini welcomes me into her home studio near the beach on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island. Flanked by bougainvillea and frangipani, it’s a calm, light-filled space. Works in progress and prototypes line one shelf, delicately layered laser-cut pieces adorn the walls, and incredibly ornate sculptures draw me in.

The works look deceptively simple, but closer inspection reveals detail that’s almost baffling in its complexity, made from tens, if not hundreds, of layers of laser-cut paper and paper-thin wood veneer. Ibbini hands me samples to touch and I’m astonished at how delicate they are, each tiny element—a flower, a geometric shape, a tiny pixel-like square—so perfect in its beauty that it’s almost impossible to imagine it can be made by human hand.

Those hands receive help from complex computer algorithms developed by Ibbini’s husband, Stéphane Noyer, a former software engineer in the oil and gas industry with a specialisation in computational geometry. Ibbini has always had an interest in the digital space, too. When she began her studies at Leeds College of Art and Design in the UK, she assumed she would become a painter, but the medium didn’t resonate with her. “I did visual communications, which is a mix of design and printmaking that works with computers, and it was the tech side that spoke to me more,” she says.

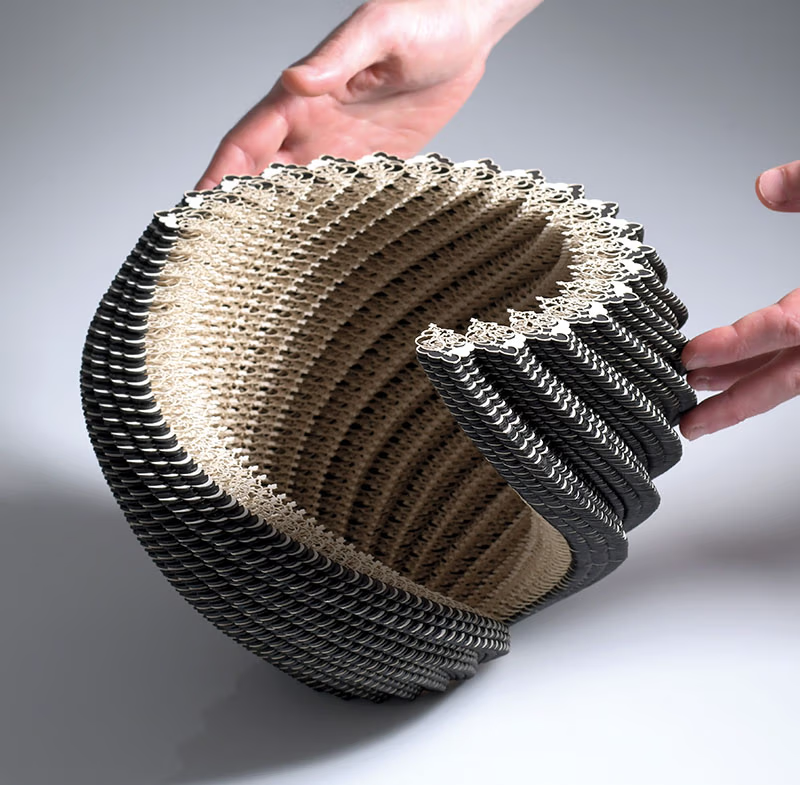

Opening image, Julia Ibbini. Above, in the Rebel Artefacts series, mathematical ideas create complex, sculptural works. Portrait, Courtesy of Van Cleef & Arpels and Tashkeel. Rebel Artefact, courtesy of Studio Ibbini.

Ibbini embarked on a career in marketing and continued her art practice on the side, producing two-dimensional works of computer-based layers. It was her discovery of laser-cutting machines at a makers’ space in Abu Dhabi in 2016 that catapulted her practice in a new direction. “I started thinking about taking the work that had been detailed and layered but that nobody but me could see and turning it into something where you physically layer the detail. I worked with paper because it was an easy material to start with.”

Ibbini begins each artwork as a drawing done by hand on a computer. Having initially used standard software like Adobe Illustrator, she reached a point where it couldn’t keep up with the complexity she sought. Enter Noyer. “He figured out how we could automate and make more intricate works, and that’s where the custom software started,” she says. They now work together full time, Noyer developing the algorithms that realise Ibbini’s ideas.

“This gives me a 3D rendering and I can decide whether everything is placed the way I need it to be,” she says. “Then we send it to another set of algorithms which creates a series of layers that a laser machine can cut.”

Next, every layer of paper, ranging from tens to hundreds depending on the piece, needs to be assembled by hand, glued with tiny brushes and aligned with little margin for error. Ibbini’s work is pushing material boundaries. “We fail every day, and it’s part of the practice,” she says. “If you’re not failing, you’re not moving forward, especially when you’re trying new materials.”

Symbio Vessel The studio explored the notion of a traditional vessel—utilitarian and simple—but introduced abstract structural modifications and complexity through algorithms and computational geometry. Courtesy of Studio Ibbini.

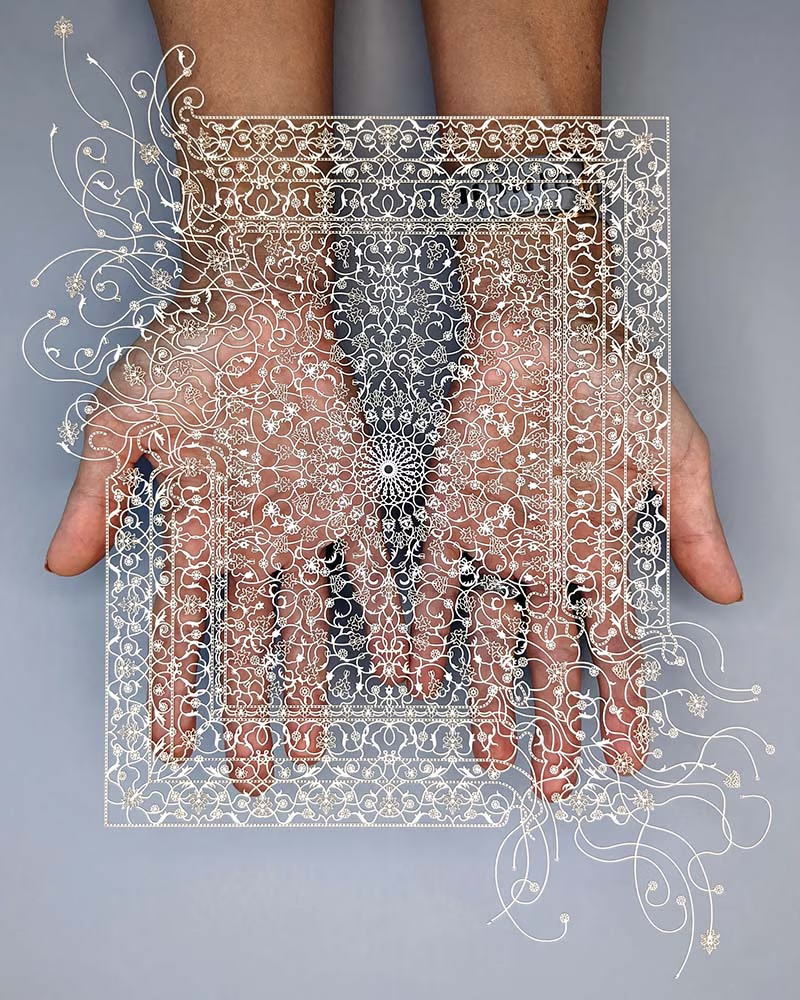

On the wall, a piece called Ornamental Mixtapes is anything but slick and minimal. Inspired by the repeating ornamental motifs of antique Persian carpets, it looks like a garden gone wild, flowers breaking free of the walls that enclose them. “A lot of the work we do is very systems- and rules-based, but with this one we wanted to go freehand a bit. You can never keep a garden in check. It always wants to go off and outward and we just wanted to let this one go,” Ibbini says.

On another wall, what look like disintegrating carpets—the Dissolves series—are inspired by fragile fragments of tapestries kept in museums. “The idea was to convey something that was fading away using the very latest tech, we used a hugely complex algorithm to help us do this. They’re intended to look like carpets with four-point symmetry, but conveying an idea of loss. It’s a sense of tension, juxtaposed with the tech behind it,” she says.

I am fascinated by her Symbio Vessels, spiralling layers of black and white that draw my gaze like a vortex when I peer into them from above. Made from laser-cut layers of paper based on a traditional floral motif, the vessels spiral around an arc. Here, Ibbini explores the notion of a traditional vessel, intended to be utilitarian and simple, but they introduce abstract structural modifications and detail with computational geometry. They look organic, like snake skeletons, their delicate ribs twisting upwards. Ibbini tells me that other people see seashell patterns.

These pieces have garnered attention around the world, winning the 2019 Van Cleef & Arpels Middle East Emergent Designer Prize, and being commissioned by collectors from the US, Switzerland and Australia, among others. An algorithm developed by Noyer takes what would have been a two-dimensional flower motif on a completely different path.

“You recognise something traditional, and something quite simple, but we create complexity by repeating it,” she says. The motif changes in size depending on the diameter of the vessel, creating rotational lines with a twisting void in the centre. “It’s a very simple concept,” Ibbini says. “I say simple, but they’re awfully difficult to make. But I feel like if it’s not hard enough to do, was it even worth making in the first place?”

Ornamental Mixtapes is a series of works inspired by repeating ornamental motifs drawn from antique Persian carpets. The delicate tendrils of flowers and leaves grow outward, eschewing symmetry towards a more organic form. Courtesy of Studio Ibbini.

On the wall, a piece called Ornamental Mixtapes is anything but slick and minimal. Inspired by the repeating ornamental motifs of antique Persian carpets, it looks like a garden gone wild, flowers breaking free of the walls that enclose them. “A lot of the work we do is very systems- and rules-based, but with this one we wanted to go freehand a bit. You can never keep a garden in check. It always wants to go off and outward and we just wanted to let this one go,” Ibbini says.

On another wall, what look like disintegrating carpets—the Dissolves series—are inspired by fragile fragments of tapestries kept in museums. “The idea was to convey something that was fading away using the very latest tech, we used a hugely complex algorithm to help us do this. They’re intended to look like carpets with four-point symmetry, but conveying an idea of loss. It’s a sense of tension, juxtaposed with the tech behind it,” she says.

I am fascinated by her Symbio Vessels, spiralling layers of black and white that draw my gaze like a vortex when I peer into them from above. Made from laser-cut layers of paper based on a traditional floral motif, the vessels spiral around an arc. Here, Ibbini explores the notion of a traditional vessel, intended to be utilitarian and simple, but they introduce abstract structural modifications and detail with computational geometry. They look organic, like snake skeletons, their delicate ribs twisting upwards. Ibbini tells me that other people see seashell patterns.

These pieces have garnered attention around the world, winning the 2019 Van Cleef & Arpels Middle East Emergent Designer Prize, and being commissioned by collectors from the US, Switzerland and Australia, among others. An algorithm developed by Noyer takes what would have been a two-dimensional flower motif on a completely different path.

“You recognise something traditional, and something quite simple, but we create complexity by repeating it,” she says. The motif changes in size depending on the diameter of the vessel, creating rotational lines with a twisting void in the centre. “It’s a very simple concept,” Ibbini says. “I say simple, but they’re awfully difficult to make. But I feel like if it’s not hard enough to do, was it even worth making in the first place?”