Where history is still being written

The grand hotel La Mamounia marks a century as Marrakech’s most luxurious address.

By Alice Morrison

Horns blare with indignation in the heart of Marrakech. The orange trees that line the grand Mohammed Vl Avenue are in sweet-scented blossom. Camels lounge in their shade. “City walls tour, Madame?” calls the driver of a green carriage drawn by two fine grey horses tossing their manes. I decline and head away from the tall minaret of the Koutoubia mosque to the discreet entrance to Morocco’s—and some say the world’s—finest hotel, La Mamounia.

The imposing doorman, dressed in a long red cape and fez, swings open the door for me, greeting me with a smile and a “Bienvenue”. I plunge into the calm, elegant lobby, where I am given the dates and milk flavoured with almonds with which visitors who have travelled far are traditionally welcomed.

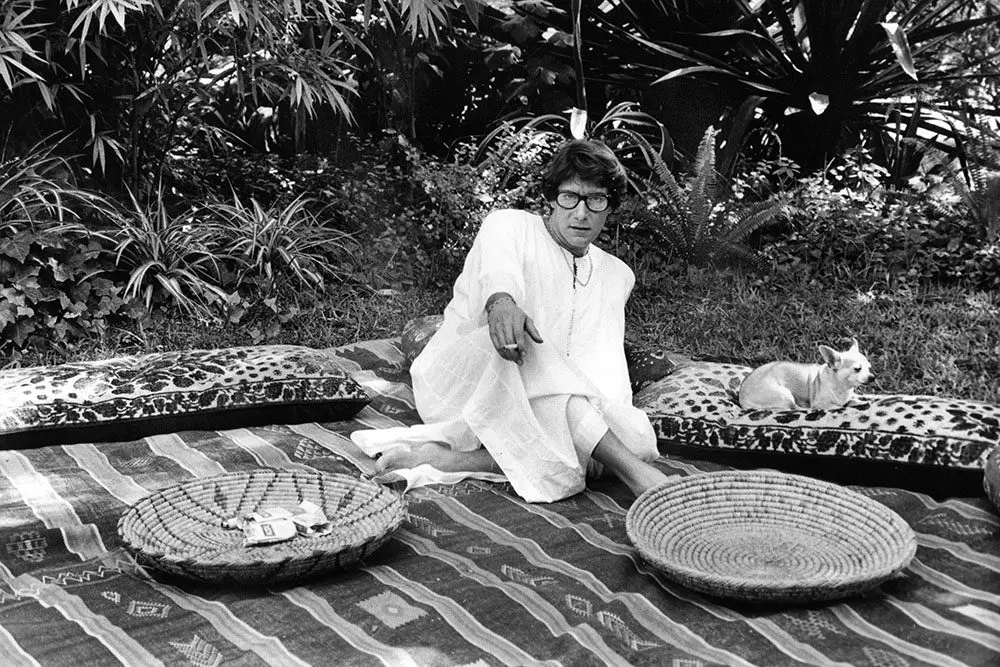

“It is the most lovely spot in the whole world,” is how Winston Churchill described the hotel, where he came regularly to paint and relax. His paintings of the garden hang in the Churchill War Rooms museum in London and he lends his name to the hotel bar. But he is far from the only notable guest; a storied guestlist includes Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Yves Saint-Laurent, Omar Sharif, the Rolling Stones, Franklin Roosevelt, Gwyneth Paltrow and countless others.

La Mamounia is celebrating its centenary. It was founded in 1923 by the Moroccan Railway Company and has everything that you would expect of a luxury hotel: 135 guest rooms, 71 suites, three private riads, four restaurants (Italian, Asian, Moroccan, and international), a huge swimming pool, now with a wine bar beneath, four bars, two tea rooms, a nightclub, games room, gym, tennis courts and a cinema. While Marrakech now has a wide choice of five-star hotels, there is only one Mamounia.

The hotel has history on its side, but it also works hard to enhance its uniqueness. A good example is the new Pierre Hermé salon de thé which was refurbished as part of the hotel’s 2020 makeover by Parisian architects and designers Patrick Jouin and Sanjit Manku. You pass by the antique camel marble statue in the calm dark of the old lobby into a dazzle of light from the very modern crystal chandelier reflected in a fountain pool. Above is an exquisite carved and painted cedar ceiling, the traditional decoration of a Moroccan palace.

Tea is important to this culture, and here it is complemented by exquisite French pastries from one of the world’s great patisserie chefs. Pierre Hermé has even put his own spin on Morocco’s famous corne de gazelle (the horn of the gazelle) which is a delicate pastry stuffed with crushed almonds and shaped like its namesake. Usually, it is about the size of a thumb, but Hermé’s versions are giants and taste delicately different. When I ask what he puts in them, lips are primly sealed, but I am given one nugget: “He includes a touch of orange.”

The hotel has its own perfume, scented with dates. It has its own wines, from vineyards in Morocco, and a champagne produced for them by Taitinger.

Founded in 1923 by the Moroccan Railway Company, La Mamounia today offers 135 exquisite guest rooms, 71 suites and three private riads. Behind traditional wooden doors, Moroccan craftmanship is combined with contemporary design. Yves Saint Laurent is among the hotel’s famous guests. First visiting in 1966, he credits La Mamounia with bringing about a creative renaissance. All photos courtesy of la mamounia; Saint Laurent by Guy Marineau.

It is one of the signatures of La Mamounia, this melding of cultures to create something unique. The hotel has its own perfume, scented with dates. It has its own wines, from vineyards in Morocco, and a champagne produced for them by Taitinger.

I live in a small village in the Atlas Mountains, where the food, like life, is simple, organic, and repetitive. Imagine my delight when I open the exotic menu of L’Asiatique, overseen by multi-Michelin-starred French chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten. The food is genuinely extraordinary: foie gras dumplings steal my heart and I would be willing to sell my soul for another helping of the lobster noodles.

Although the restaurants are exquisite, my favourite thing about La Mamounia remains the eight acres of gardens that give the hotel its name. In the 1700s, the king at the time gave a house and garden to his son Mamoun as a wedding present. Prince Mamoun used to host magnificent parties amongst the trees and flowers.

Wide avenues of noble palms and architectural cacti are interspersed with deep rose beds. Marrakech is called the rose city because of the warm colour of its walls but it could equally refer to the flowers which grow so abundantly here. Olive trees spread their sturdy branches over the lawns, and the gardener tells me that some of them are 300 years old. The olives are pressed into La Mamounia’s own oil. A kitchen garden supplies the restaurants’ vegetables.

Last year was a boom year for the hotel, and when I visited occupancy was at 80%. I asked the general manager, Pierre Jochem, what keeps it special 100 years on. “Since we first opened in 1923, La Mamounia has been a symbol of traditional Moroccan hospitality and a classic example of the great age of grand hotels. Our history is still being written, and while our luxurious style is timeless, we move with the times and offer everything a modern traveller is seeking. Guests love the craftsmanship of our interiors, our gardens, spa, world-class restaurants and our location at the edge of Marrakech’s old city, but the true treasure at the heart of La Mamounia’s success is our warm and gracious staff.”

It’s the kind of thing you expect a GM to say, but there is a heartfelt echo when I talk to one of the hotel’s newest recruits, Ahmed Elcadi. He has just joined the team, having earned his hospitality degree. “Do you like working here?” I ask. “To be honest,” he says, smiling with pride, “it is a privilege. You are part of history, you are writing history even in a small way.”

Alice Morrison is a writer and adventurer based in Morocco. Her latest book, Walking with Nomads, is shortlisted for the Edward Stanford Travel Book of the Year.